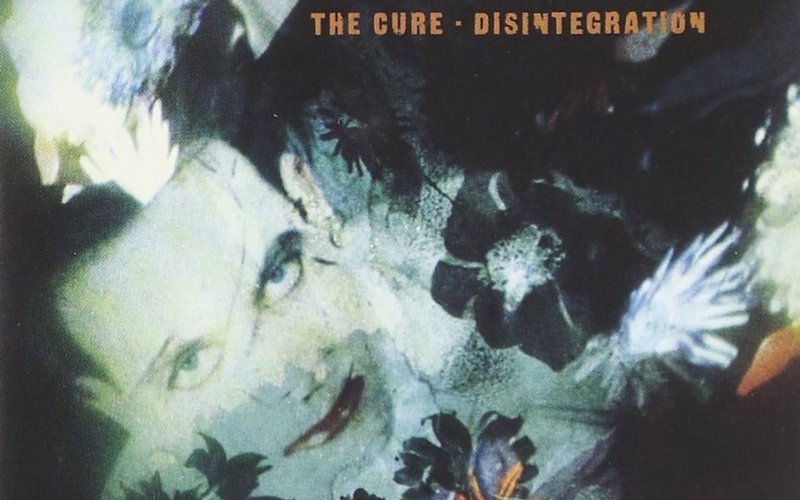

On Wednesday, May 22nd, KEXP is celebrating World Goth Day, declared "a day where the goth scene gets to celebrate its own being, and an opportunity to make its presence known to the rest of the world. We’ll be playing all the darkness all day long on-air from 6 a.m. to 6 p.m. PT, as well as revisiting some of our goth favorites – like The Cure’s Disintegration, which turned 30 earlier this month.

You hear the chimes first.

A low hum reverberates in their wake.

Then a crash, and the skies open with the sound of strings and synthesizer thrusts. Chimes and swells, back and forth, again and again. And just when things feel like they couldn’t be blissful enough, a slippery note slides and cuts gracefully through the sonic tapestry.

Words murmur in the air. They echo and disintegrate into barely discernable musings about the end of the world. His voice is young and weak as he coos about being old and in pain. It feels like both the beginning of a new day and the rolling of the credits.

It’s the sound of falling apart. It’s the sound of picking yourself back up.

“So, were the last 29 years of your life miserable?” my wife asks our friend from the back of the car. She means to ask if just his 29th year was miserable, but we all laugh about the hint of truth in her accidental phrasing.

So much is made up about 27 – mostly due to the destructive narrative of rock stars who never made it past that age. But as I’ve entered 29 myself, I’ve found more and more people willing to wax poetic about their misery in the shadow of turning 30.

It’s obviously an arbitrary benchmark we’ve made for ourselves. And almost anyone I know over 30 is quick to dismiss it being “that big of a deal.” A surely they’re right. Because really, why does it matter? You could live to be 102-years-old or get hit by a truck tomorrow. When you look at it on that spectrum, it all feels arbitrary.

And yet.

Despite what we might tell ourselves, despite all logic, despite what we’ve seen firsthand in others, this year becomes a crucial milestone that has to be reckoned with. Maybe it’s feeling the need to have a house and kids. Or a career. Or just some semblance of knowing where your life is going. You become a legal adult at 18, a drinking adult at 21, and then you wait out a long gap question marks before you’re a functioning adult at 30.

In a way, it’s comforting to know someone as accomplished and inspired as The Cure’s Robert Smith could feel these pressures too and was equally filled with the existential dread of things he might not accomplish by his third decade. Where I might binge watch Nathan For You and give my dog a TedTalk about my self-doubt, Smith wrote Disintegration.

Smith famously found himself having a crisis when he turned 29, worrying that all masterpiece albums were written while artists were still in their 20s and feeling like he hadn’t written his own yet. The Cure were certainly successful, especially just coming off the smash-hit “Just Like Heaven” from their previous album Kiss Me, Kiss Me, Kiss Me. His depression and anxiety were immense. He’d turn to LSD and hallucinogenics to combat the feeling.

“It's just about the sense of falling apart that I can't ever seem to shake off,” Smith described Disintegration to Much Music in 1989. “But I think it's true for everyone.”

Disintegration may have been the result of Smith’s dread of aging, but it’s also an album that couldn’t exist with this muse. While it’s undoubtedly one of the band’s finest moments, it had to come from some of Smith’s worst feelings. The songs feel timeless because they’re written so well, yet they aptly capture the sensation of this particular moment in life. The time when you feel like you have to hurry the fuck up and get your shit together.

Maybe it’s a relative. If you’re already in a successful rock band, “getting your shit together” means writing a classic record. Whereas the rest of us have to figure out how to maximize our HSAs or whatever. Smith’s self-imposed pressure to beat the clock thrust the band further into greatness, even if they were already doing exceptionally well for a band of musicians in their late-20s.

The wicked wheels of time continue to churn along and now Disintegration finds itself at 30. If albums were sentient and self-aware, I wonder if Disintegration would feel accomplished at its ripe age. It’s received plenty of accolades over the years, with rave reviews upon its release and a flurry of retrospective pieces like these about its importance over the years.

But I doubt Disinitegration could be content. It’d still be looking at Abbey Road as the unachievable benchmark while side-eying modern works by younger artists garnering acclaim even earlier on in their careers.

While I can think of albums Disintegration has inspired, I can’t think of an album that sounds quite like Disintegration.

It’s not just the whimsical, pop splendor of “Pictures of You” or the rigid gloaming of “Lullaby” that make Disintegration such a touchstone in music. Nor is it the simple, romantic genius of “Lovesong.” It’s a mastery of atmosphere without becoming atmospheric. Each song on the record exists on its own, punching through the speakers with intricately crafted hooks and gothic poetry.

Smith’s point about everyone feeling like they’re falling apart is amplified by the structure of the record. The instrumentation and production throughout the record are as solid and intentional as you could ever hope for. Everything is so airtight. Guitar parts sound precise but given a languid feeling with finely tuned reverb. Yet in the middle of all this, Smith’s voice feels like it’s crumbling. His melodies rise and fall, reach out from the abyss before collapsing back in.

His words and voice are a foil to the impenetrable design of the record. It’s like a sinkhole materializing out of concrete. And all of this is a compliment, of course. You can feel the human spirit behind each instrument, but no one sounds more in the weeds of humanity as Smith when he sings “If only I could fill my heart with love” on “Closedown.”

And this is really what falling apart feels like. To breakdown, you have to know what “put together” looks and feels like. It’s when you see it all around you or see it in those you admire and wonder why you can’t be that too. That’s hard to not take personally. How can you expect to be better than you are when all you feel like doing is crumbling into dust?

This push and pull is central to the record and central to the real-life experiences informing it.

On the album’s title track, the feelings all come to a head. For eight-minutes, Smith and the band give an anxious meditation. The bass line rolls in repeat in line with the spiraling drums while Smith spirals out of control. You can hear effects that sound like the shattering of glass crackling against stuttering keyboard pulses.

“Now that I know that I'm breaking to pieces, I'll pull out my heart and I'll feed it to anyone,” Smith wails in the song’s most impassioned stretch. He practically yells the words. It’s a call out from desperation. It’s a cosmic collision of instrumentation; a maximalist screed that channels that feeling you get in your stomach when you don’t see a way out.

“How the end always is,” he repeats.

It’s funny in retrospect, knowing that this would be far from the end of The Cure or Smith. But it felt real at that time. When you hear it on the record, it doesn’t feel like an exaggeration. It’s a spewing out of guts that most of have felt or will feel or are currently feeling.

The end always is.

Layer on the black eyeliner and cue up Siouxsie Sioux — it's World Goth Day!

In Another of World Goth Day, KEXP takes a look back at the gothic cowboy aesthetics of Carl McCoy's Fields of the Nephilim

KEXP's DJ Abbie chats with the legendary artist about expressing herself truthfully despite "notions of discomfort"