I’ve lost track of the number of times I’ve written the words “I hope you’re well” in an email. In truth, it’s not a phrase I put much thought into until the pandemic hit in March of 2020. It existed in the pantheon of “just circling back” and “per my last email,” the hall of fame of digital communication courtesies. But when living in a world on fire, you start to reconsider even the most minute of interactions. How do start an interaction with “I hope you’re well” when you don’t even know if it’s safe to go outside? You begin to question, “Am I being sincere or am I just going through the motions, clinging to some semblance of normalcy?”

When I first saw the title of Lionmilk’s latest record, I Hope You Are Well, and heard the lead single title track, I was taken aback. The wordless melody played through what sounds like a Rhodes piano began to melt away my cynicism. The ambient hums and the swirling keys craft a moment of calm, a call to breathe. It felt like a much-needed embrace from a friend.

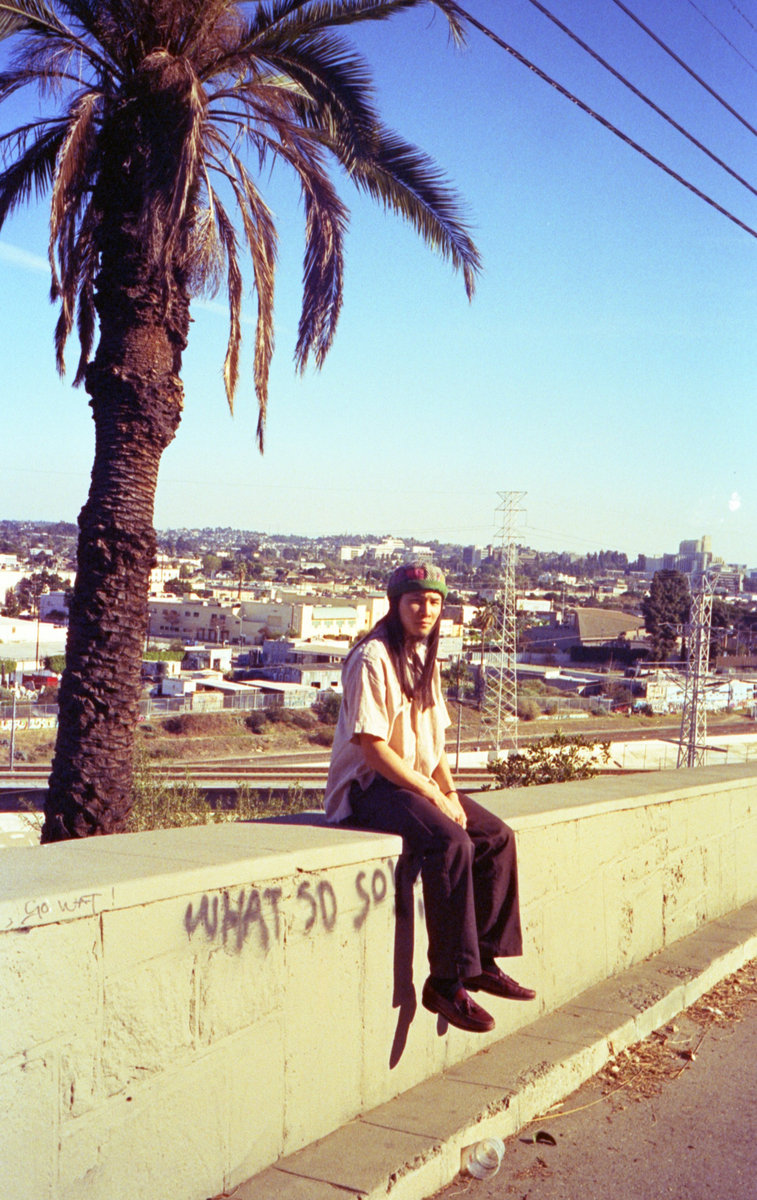

As it turns out, that assumption wasn’t far off. The moniker of Los Angeles-based musician Moki Kawaguchi, Lionmilk originally released I Hope You Are Well as hand-dubbed cassettes with original artwork that he hand delivered to the mailboxes of friends and family he thought might be struggling with depression or anxiety during the pandemic. The record took on a second-life when it was given a wider official release in early 2021 by L.A.-based label Leaving Records (who also re-released Lionmilk’s excellent 2018 album A Real Rain Will Come). The track titles themselves feel like personal mantras or affirmations ¬– “We Start Again,” “Made It This Far,” “Necessary Growth,” “Good Things Happen, Too.”

Within Kawaguchi’s work, there’s both a welcoming, consuming sense of peace and exemplary musical performance. In his previous works like A Real Rain or 2019’s Visions in Paraíso, Kawaguchi flexes his beat-making prowess. He exudes the L.A. ethos felt through Stones Throw alumni like Madlib and Kiefer, blending together jazz, hip-hop, and ambient production with therapeutic results. I’ve described his music to friends as a cross between Flying Lotus and Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood. His works this past year – including a stellar collaboration with MNDSGN titled Forever In Your Sun – increasingly became more spacious and less rhythmically oriented, a reflection of contemplative space Kawaguchi found himself in.

I recently had the chance to catch up with Kawaguchi to discuss his record, using music as a means of healing, and the radical act of introspection. Read our conversation below.

KEXP: I read that you got your start in classical music as a kid before entering a jazz program in high school. And jazz feels still like a pretty big element to your work today. I'm curious about your background and what drew you to your style of playing?

Moki Kawaguchi: I started classical when I was a kid, my mom put me into lessons. My family's from Japan and they immigrated here in the 80s and they were the classic like, you know, 'You're born in America. So we want you to do everything," basically. So she had me doing piano lessons because she never got that as a kid. So, big blessing to her for giving me the opportunity to learn piano. And same with my brother. He was getting lessons too.

I was composing a lot when I was younger, I was writing music, like note-for-note because I didn't know what chords and stuff were back. So I just wrote. I composed on paper. I was always composing throughout my youth. Wrote little piano pieces and little compositions for my friends and stuff. I went to high school, an arts high school out here in L.A. I went in for the classical piano program, but then they had a really good jazz program that I wasn't aware about. And I asked him what I need to do to get in there. And they told me to learn all this stuff. So I spent a summer just cracking down, learning from records how to play jazz music, then they let me in. From there, I just kept on growing, that high school really kicked my booty. They were really intense. I guess now I look back, I guess it's a college-level program that they were doing because they were really intense.

[From there, I moved to New York for the New School for Jazz. And I realized that I wasn't really liking the jazz scene, I guess, because it was just off all of those, but it was just full of douchey people. I really wasn't about that because I was all like, "I want to make music that's honest" and all this. And I'm not saying every jazz musician's like this, but I just met a bunch that were just egotistical and wealthy and just made music just to shit on people. I wasn't really about that. So I started to hang out and make friends with a lot of the underground musicians in New York. And that led me to the hip hop scene out there and electronic music scene and punk scene, all these different scenes that were outside of jazz. I felt a lot more comfortable in those scenes than in the elitist jazz community that was in my foreground.

From there, I was doing all kinds of jobs while I was in school. I was working like three jobs to pay rent and pay off loans and stuff. And I was working as a fabricationist, like a construction worker in some way. A handyman. I was just working there every single day, all day, and it just burned me out and I was like "What am I doing with my life?" It made me realize I needed to make a change. So I moved back home to L.A. and now we're here. I'm doing my thing.

It feels like you've always kind of been called to create. Right. Your earliest music experiences were creating songs and it seems like jazz, a lot of it is improvisation. I'm curious if that resonates for you or what appealed to you about jazz in particular and all these styles that you've ended up adopting.

I was listening to jazz all the time because my father was a big jazz fan and he had a bunch of Count Basie and Duke Ellington and Bill Evans, Oscar Peterson. All these records were at home and just a lot of Brazilian music, too, like Antonio Carlos Jobim – samba music from Brazil. And I had a neighbor that was a big jazz listener and he would come over and burn me CDs, actually. [He'd] burn my father and my family and me CDs of Duke Ellington and all of his favorite musicians and I would have the looping all the time. I guess that's how I had an affinity [for] jazz.

It's cool to hear going to New York and getting into these other scenes like hip hop and punk. How did that impact you artistically? How have all these different influences taken shape in the music you're making now?

When I was growing up, I was always listening to all kinds of music. Not just jazz and classical. My brother was really into hip hop and rap music, and I was listening to a lot of 50 Cent and Snoop Dogg and Dr. Dre. And I was really into metal music too at some point I was listening to a lot of Megadeth and Metallica. You know, the young days. I was really into skateboarding when I was younger, so I was listening to a lot of hardcore music. All my friends get pumped up to that and we'd all go skate. I think there's just a lot of shades to life. I've just been open to all of those different colors of music. And I never really discriminated. I didn't shoo off any kind of music. I always was found some kind of way of enjoying any kind of sound, I guess.

It feels like sentiment has like become more open-minded, generally. Generations that are making music now where it used to be so prescriptive or it scenes to be more prescriptive. "If you're punk, you listen to punk." But now there's open-mindedness. It's really cool to see you and other artists adopting that and being open to that in your music.

I think, in the end, music is just music. There's only good music and bad music. And that's relative to each person. Every person gets to decide what they like and what they don't like. So in the end, it doesn't really matter what genre it is. It's if you like it or not, basically.

Your records vary in style and influence, but you have this really cool soul-jazz, ambient electronic sound that's permeated a lot of your most recent records. I'm curious how you started to create the current [music style] you're working with today?

I guess just through all the experiences in life. I think I make music to represent the time and the experiences that I'm going through at that time of my life. It's kind of like a diary, in a sense. Y'all are listening to my diary entries through songs and rhythms and whatnot, so it's all culminating in that.

That seems like it leads maybe into your latest record, 'I Hope You Are Well,' which was originally released as home-dubbed cassettes that you dropped in mailboxes of your friends and family who you thought might be struggling with anxiety or depression in that early stage of pandemic. I'm curious where you first came up with this idea to create these tapes to give to your friends and family and what the response was from people you gifted it to.

So this tape came into existence just over the years... I was recording all kinds of piano improvisations or piano pieces. It's been collecting for about two years. Whenever I would feel anxious or depressed – and that was a lot throughout the past few years of my life – I was expressing that through music. It always helped me feel better. That's the power of music, in a way. It helps you get through a lot of the tough times in your life. During those moments, I couldn't express it in making a beat or making all "hype music." I would feel more connected to like my improvisational side. So I guess that's how I represented those emotions by playing solo piano music or making loops and such.

That was just culminating over the years and this pandemic happened and it just felt like... and that's the thing, this pandemic happened and my friend was going through hell because he was all alone and he was, you know, like a lot of people, was going through a lot of depressing phases and anxiety and not knowing what to do. I was talking to him and it just felt like it wasn't helping. It felt like words weren't the best tool for me to use to help him. So I started making a mixtape for him. It was like side-a being like a mix of different artists like Ahmad Jamal, a lot of different kinds of artists on the softer side. And side-b was the music that you hear [on] I Hope You Are Well. I gave it to him. I gave it to my mom and I gave it to some other friends. And it seemed like it was helping them because they could focus on something else that isn't the world burning.

That's such a brilliant idea because I feel like, I don't know, it's been hard to talk to people. I mean generally [talking] about depression can be hard for people, but especially in this pandemic time. Music can be maybe that conversation or the words you want to say but can't say.

Yeah, I think I'm not a person that could talk really well. I can express it to you in music... Talking is not the first thing that I do, you know. I can tell you how I feel through music and I can hopefully express those emotions that I feel and you and the listener can relate in some way.

I read in an interview with you about your creative process, sometimes you'll try to conjure an image in your head that aligns with a certain feeling that you're trying to translate through your music. I'm curious about that and what were some of the images you were thinking about when you were creating the music on I Hope You Are Well?

All kinds of images, I guess. Mostly emotions, just of hopelessness and just feeling self-loathing – all the negative emotions, I'd say. Just all the different kinds of dark things that could roam free in your head. I feel like everybody has moments in your life where that just takes over your whole psyche and you can't really control it. That happened, I'd say, quite often back then to me, and I didn't really know how to deal with that. Whenever those emotions were overwhelming me, I would try to sit down on the piano and imagine what could help me feel better. A few chords and melodies would soothe me and then that would lead to another thing and then that would build to another story. And then my mind would create an image of a scene, I guess. Maybe it's like an ocean, a calm ocean, or like a rainforest. Something related to nature most of the time. And using the imagination to paint in sound.

I love that. That feels very meditative or mindfulness sort of stuff maybe.

Right. It's also like an image-based concept, but it's also very spiritual, for me, at least. It's kind of like asking my ancestors for guidance or asking my inner-self for guidance. And I think the expression is the path to realizing what I need to do or what I need to do to alleviate this turmoil, this internal turmoil.

Because this past year has been so tough and it sounds like you may have been struggling with depression before, was it difficult to go through that process sometimes? Were there times you were like, "I actually don't want to do this?" Or did it always just feel like a natural thing for you to do to process your emotion?

I think it's a natural thing for me because throughout my childhood I would say that I was going through a lot of negative thought processes, depression, whatever you want to call it. Music was always a thing that helped me get out of it. Just like the darkest things that would pop in your head and music would help me feel less bad about it. There was a lot of things going on in my youth that was keeping me keeping me down.

Listening to D'Angelo or listening to Debussy or listening to Sly and the Family Stone or listening to Slum Village, anything, just any kind of sound would always get me to feel like a human being again and less alone and less like the world sucks. Felt like music has always been the thing that helped me pull out of the deep end and helped me pull out of the pit. It's always been a source of expression for me and I was able to express myself, which I'm very thankful for. Because without that, who knows, I would have probably been in a very bad place [laughs].

When you go back and listen to any of your recordings now, do you remember those feelings or is it just totally different now? Does it bring you peace?

I think it's a lot more peaceful now because in the moment it might have been very hectic and all that, but I've learned to grow from them and I've learned to move on from those experiences and move forward instead of sort of retracing steps, you know? And I think that's an important thing in life, is to keep moving ahead and learning from experiences. I think when I listen back, it's like, "OK, I've gotten this far." It's like a reassuring feel. It's like, "You were there before and now you're here and you've worked it out. Pats on your back."

Like you said, it's like a diary, right? Going back and reading and you're like, "I was so stressed about this thing, but now, look how far I am. Look where I'm at now."

Yeah. It's like at this point in my life I was suicidal or something. Oh, look at that, I'm a little better now. Good job. You're fighting that demon inside of you.

That's awesome, and it must be cool to have a document of that like personal growth that you can reflect on.

When I was younger, I was definitely not thinking of it like that. I just needed to express myself. I think I am thankful for my younger, more "just do it" kind of personality. I am thankful for that.

I was curious about the title as well. I Hope You Are Well. I feel like that's a phrase that's become ubiquitous with like emailing people [laughs] and there's maybe been some like... I feel like I've seen people [say] that's a disingenuous phrase or something. But here in this context, it feels really sincere. But I was curious how you landed on that title and what it means for you?

I think that's what it means, I hope you are well. Just straight up. I hope you are getting through whatever problem that you are. I hope that you can find the peace within you to move ahead and grow from it and not look back. I can see how that could be synonymous to like email culture, but I think I imagine saying it in person more than anything, really. I feel like when people read it, it's like, oh, I hope you are well – from me. That's how I at least want them to see it. I really hope you are doing all right, because I really do hope you are.

I think that's the thing with this world, we're all very not trusting of each other – for good reasons – and we're all very divided in how we think and we divide each other even more by the actions that we do. I don't want to do none of that. I just want people to be together... That's the thing, it comes back to that. I really hope that... Because I can't live your life for you. I can't do anything to really change how you think or how you go about your life. That's not something I could do because I'm just another man like any other person around the world. All I could really do is wish you well. I wish and hope that you are in a better place than yesterday, at least.

Yeah, I love that. It was refreshing seeing that phrase and listening to it with your music because, for me personally, it was just a reminder that this isn't a flippant phrase. This is genuinely hoping people are well. Especially during the pandemic, I feel like it's been hard to like... How do you check in on people, especially when the world is going crazy and you're saying I hope you're well? I just really appreciate the genuineness that you're bringing to it.

I couldn't really think of anything else to say. At first, it was to friends and I was saying, like, "I hope you're doing good because I haven't heard from you." But then it became like an actual release and I didn't really want to change it because that message is still valid to any person out there that's willing to listen to this music, open to the music at least. It's like, I might not know you, but I still really do hope you do alright. Even if you aren't my friend or my family or I don't know you, I still hope that you're doing alright.

Besides just this record, you were really prolific last year, you released a number of records on your own as well as some collaborations. Did you find it challenging at all to stay creative during this really crazy year or was it just kind of naturally flowing from you?

I did have difficulty in the beginning because it was so wild, such a new thing. This has never happened before. So I was having difficulty adjusting to it in the beginning. But like I said before, whenever there is a problem or there is a tough time that I'm going through, music always helps me. And I think I did just that. I was having a hard time then, I was like, "Okay, this is a sign. I got to express myself, I gotta use music to get me through this." And that's just what I did, I guess.

Listening to the records you released in 2020, it feels like a lot of music you were releasing kind of became less heavy and more atmospheric with each one. It sounds like they were all recorded at different times, but I was curious if that was like an intentional choice to lean more towards your more atmospheric work than the more beat-heavy [music]?

Yeah, I wasn't really hearing beats this last year. I just couldn't get myself to feel "up" like that. I was feeling more... I guess not feeling "beat-like" like [laughs]. Just feeling like I needed to express myself in a more improvisational, growing, changing way.

One of the releases last June was Healing for a New Tomorrow which you recorded with violinist John GK, and you donated all the proceeds to the Bail Project. And that was another record you described as being about mental, emotional, and spiritual wealth. I was curious about the genesis of that record and how you saw it responding to the world or not?

Well, John and I were working on some music like in 2019. All the stuff that you heard on that record was recorded in 2019 and we were just sitting on it. The whole riots were happening and Derek Chauvin was, you know, he did the thing. Black people were getting killed and we couldn't sit around just not doing anything. So we had to do something about that. All these protesters were getting thrown into jail and I can't get myself wrapped up in the rage and the anger of everything, I had to go the other way.

We both decided that this is how we can help instead of going the other way, we can help with peace. Calming people. Or at least help try to help people to calm down and ground themselves. Because we didn't know what was going to happen next. Protests were escalating every day and who knows, the government was about to pull out the military on us. And then who knows? It could have been like Myanmar shooting people and killing a bunch of people – we didn't know was going to happen. So at that point, I was like, OK, we got to prepare. But not with anger, not with rage, and prepared with peace in mind and be able to have the mental stability to approach whatever situation comes next.

I can remember that time, too and just a lot of music didn't sound good to me, personally...

Yeah, it was crazy! Like, I can't listen to really "up music" when I just watched George Floyd get murdered. It's tough. And you hear about Breonna Taylor and you hear about Tamir Rice getting murdered. It's like these kids get murdered. I can't listen to bumping music. It's like, I have to sit with myself and process these emotions. I can't get myself to be happy, because it's disgusting, the kinds of things that people do, police do. We look at you look at it now, you have the little 15-year-old that got murdered. It's disgusting. Like, how can you get yourself to murder a child like that? I can't get myself to live my life normally. How can I express that, you know?

Yeah, exactly. And that's what's interesting with the music on that record, Healing for a New Tomorrow and I Hope You Are Well... it was a really radical moment that these records came out in and we're still living in. But it's sort of a radical act in my contemplating and taking time to be introspective maybe.

Hell yeah, people need to be introspective. That's the problem. People don't look inside enough and we all be doing the same problem over and over again. You know, you see racist people stay racist because they don't look at themselves in the mirror. They don't see the disgusting monster that they are. Policemen don't look at themselves in the mirror. They don't see that they're just a bunch of murderers. They think they're protecting people? Nah, you're doing quite the opposite.

People don't look at themselves enough. And people who think that they're good, you know, you always got to look at yourself. You got to check yourself. Are you actually trying to be good or is it all for show? People love to point fingers and direct blame at other people. But you've got to hold yourself accountable too. We're all humans, we all make mistakes. But you got to make up those mistakes. At some point, in your life.

Looking back at these records you put out last year and just the way you were like processing everything, did you feel like they were big lessons you learned for yourself as an artist and what you're capable of, or how you utilize art for growth or change?

I think anybody in a place of speaking to a number of people – let it be an artist, let it be a musician, let it be a dancer, let it be a public figure – I think it's our duty to spread a good message to the people that are listening to us. And I'm realizing more and more that the emotions that I feel, the honest emotions that I feel are valid and people relate to it. People around the world can relate to the feelings that I feel. And they're not alone. We're not alone in this together. We're not alone in this world. We're in this together.

And I think, as I grow older and as I meet more people and more people listen to my music, I'm realizing that the importance of being honest with the art and with the music and being honest with yourself, that's like the biggest thing. Because if I'm not honest, then what's the point of me existing and putting out music? If I'm not honest, what's the point of people listening to my music? What's the point of anything, really, if I'm not being honest and representing myself and people that trust me. So I think that's what it is. I've just got to stay true to myself and stay true to the music and reflect it in the music. As time passes, everything changes, so I have to change with it. It's not about the money, it's not about the fame. It's all about the representation of human life.

Yeah, that's what art does at its core, right?

Definitely. It's a reflection of the times. Reflection of the individual.

What's next for you? Are you working on any new projects or anything that you're excited about?

Always. Always excited. Always working on new music. I guess I can't say much, but look out for August. Something might be coming your way. Something new. Something exciting. Maybe something new will come out in between that time from now to August. Who knows? Always something new, always something exciting to look forward to.

The Chicago-based artist talks his new self-titled album and the anxieties, existential questions, an bridging genres

In a titanic two-hour interview, Martin Douglas gets a tarot reading from the Germany-based artist and they speak about the power of tarot, music, and Black liberation.

KEXP chats with the Los Angeles based artist about her debut EP, 'Spells,' out now on Leaving Records.