Elementary cat drawings and cardboard paper and an often joyful racket. The Cramps stripped down far past the essential parts to ferry through slyly funny songs about teenage lust and how the notion of death carries us through life. Cardigans and dirty Keds and a lone tom drum onstage. Two plaintive singers; one sounding like a cartoon bullfrog and the other evoking a elementary school teacher singing stoned versions of playground singalongs during summer break.

I grew up as a Nirvana kid; kind of a cliche thing to say as a 35-year-old in the year 2019. Many of the bands Kurt Cobain cited as influences I sought out over the ensuing years and either immediately loved them or spent more years trying to understand. (My studiousness paid off in many respects, traversing from doggedly deciphering what made Sonic Youth a good band to playing Bad Moon Rising on full blast and having middle-aged ladies walking their dogs look up into my open windows to figure out where that damn noise is coming from.)

Throughout my life I’ve thought about Cobain a great deal, his philosophy and approach to being an artist most of all. “Punk rock is freedom.” Punk as an ethos guiding your life rather than merely an aesthetic. As long as you like your art a little dirty, a little threadbare, and (mostly) super fucking loud and/or abrasive, you represented some degree of punk rebellion in spirit. It’s easy to detect the inspiration Cobain found in albums like Jamboree and Black Candy.

There are a lot of ways to provoke narrow-minded people. Punk represents the warfare you sometimes have to engage in to live life completely on your own terms. Beat Happening embodies that spirit as clearly as the primary colors of their music evoked.

I came home from the train station on a warm afternoon in late June 2008 to an email from a popular blogger who kept up with my work. The gist of the email itself was, “This band sounds like a band you’d love,” and he was right. I heard about how the entire first pressing of this album was sold out before the band’s ten-day tour was completed. With memories of Portland still dancing in my head — seeing Thee Oh Sees at Doug Fir while the woman I was supposed to be there with was at the bar and ended up leaving me there alone; spending the week watching this woman fall for me a little (while still having a boyfriend) and recoiling all the way back; wandering across the Hawthorne Bridge, trailing pretty far behind two women walking alongside a little girl riding her bike at 1:30 in the morning — I lazily viewed the email and prepared to unpack the contents therein.

Attached was a .zip file with ten songs, mostly clanging and hooky, sounding like they had come directly from the bowels of a Brooklyn furnace; the violence of the instrumentation augmented by the sweet and simple singalong vocal melodies. The song that opened Side B was pitch-perfect girl-group pop with multi-part harmonies; a lost classic, a crate-digger’s dream.

The first time I heard Vivian Girls’ self-titled debut album was on that warm summer afternoon in a cramped bedroom in an apartment I shared with my step-sister for a good portion of my twenties, with my one window spread wide open. Months later, when I was given the biggest of the three bedrooms (for reasons I will not divulge here), when I bought a vinyl copy of In the Red’s reissue, I played it on blast one afternoon and my two very young nieces jumped up and down during “Going Insane.” The smiles spread across their faces brought me a happiness I still see as clearly (and feel as brightly in my chest) as the day it happened when I close my eyes.

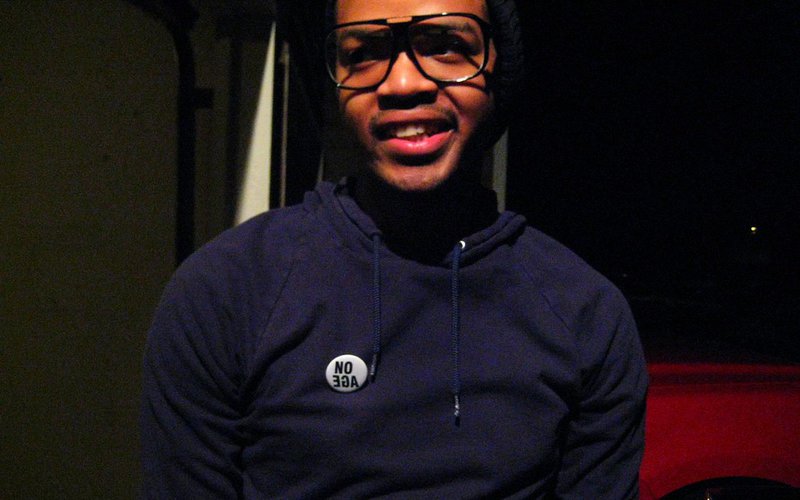

Earlier in the year, I bought a copy (on both vinyl and CD) of an album I had been eagerly anticipating; the debut full-length of a two-piece L.A. punk band called No Age. I had worn out the grooves of my bootleg vinyl copy of their loosely defined singles compilation, blending melody with noise in extremely satisfying and unpredictable ways. They were one of those bands that felt both intimately familiar and totally alien. Punk songs being torn asunder by ambient and confrontational noise, interludes like looking at a blue sky and slowly floating clouds in the far, far distance. The woozy vertigo of “Eraser,” the pummel of “Teen Creeps.”

At the time, I flirted with the idea of being a singer/songwriter — floating somewhere in the folk-punk realm, in the narrow distance between the first decade or so of the Mountain Goats and Everything Is-era Neutral Milk Hotel — but Weirdo Rippers helped me access my love of noise and unmusical elements in the context of pop music. Nouns helped me access a great deal more; an ability to channel an ecstatic bliss in making a racket, the importance of synthesizing influences to augment my own personality rather than just being a composite sketch of ideas which came before me.

Nouns instilled in me the idea that no idea is too far out there to try, the notion that I could do it all myself.

I don’t remember if she insisted or merely suggested I pick the music. My girlfriend was driving and my sense of direction wasn’t helping as we got lost trying to find the freeway heading back from Deception Pass. We just spent my birthday in Anacortes, celebrating thirty-five years on this spinning orb with a nice lunch and window-shopping at the record store. (I bought something, but a $5 Dogbreth tape is slight compared to the hundreds of dollars I’ve spent on individual trips to record stores in the past.) I chose “Exhibitionism,” the lead track from Institute’s 2017 LP Subordination.

My eyes jumped out of the window and looked as far up as they could. Trees and green as high as the eye can see. Two-lane roads winding around and around and around Fidalgo Island. A bay as small as a lake. It’s still consider a bay, isn’t it? Or is it called something else? Anyway, there was a boat on the inner edge, in a shadowy spot elusive to the afternoon sun. It looked like the images slapped on postcards. “Exhibitionism” feels like a sprint through the woods after all, and I have no doubt it was psychic intuition leading me to select that track.

When I turned thirty, a close friend of mine and I had a very involved discussion about how the breadth of taste of obsessive music fans tend to narrow when they reach this particular milestone. How after your twenties, you stop searching for every new, hot thing (or a bunch of super fledgling things not many people know about yet) and settle into the kind of music you know you like.

I have to admit there aren’t an overwhelming array of punk artists whose work I stay absolutely current with these days (though I still listen to a fuckton of punk music), with all the new music to enjoy, new music to assess, new music to obsess over (especially with many of my favorite hip-hop artists putting out anywhere between two and six new releases every year). This is the work, the curse of being a music journalist. Before my first freelance check for Pitchfork came in the mail, another close friend warned me I would have much less time to enjoy music when I start writing about it for a (partial) living.

Ever since the 2015 release of Catharsis, Institute has been a band I’ve tried to follow very closely. For starters, I’ve been doing my best to stay periodically updated on Sacred Bones’ release schedule since they dropped the Men’s Leave Home in 2011. (Immaculada, the band’s debut, is my enduring favorite of theirs. Sorry to all of my friends who love the Jesus Lizard and swore by Leave Home partly because of it.) Secondly, Institute is emblematic of the kind of (relatively) straightforward punk music I enjoy the most; monotone vocals and sardonic lyrics; snarling, growling, blaring, whining guitars; a pace fast enough to do intense cardio along with; a punchy recording fidelity where you hear bones crunch.

While the strains of “Exhibitionism” broke out of the speakers in her Honda, I hummed the main guitar line and softly pat my legs as if I were drumming on them. Eventually we found the freeway.

A mildly famous punk musician once subtweeted me in a rant rallying against people who call themselves art-punks whose tastes are "fucking boring." It was far from my first brush with punk dogma and it most certainly wouldn’t be my last.

Wimps have been one of my very favorite Seattle punk bands for almost a solid decade, partly due to how much I relate to their songs. The quickest way to my heart is through my stomach; the second-quickest is through my ears with a catalog of catchy, sprinting tunes about sleeping and pizza and the ennui associated with being uninspired to do laundry. As I’ve mentioned in this space before, few bands are better at sensationalizing the mundane existence of being (un-)comfortably settled into adulthood, of feeling the crunch of advancing in age, of Earth spinning around the sun too quickly and being the old guy at the party.

Do I love Wimps because my life is boring? Because I am boring? Because I want to feel good about getting older? Or is it because skateboarding through everyday life is just as weird and funny as the weirdest and funniest one-time experiences? Because I can hold Wimps songs up like a mirror, refracting my life and sending it through the air while middle-aged ladies walking their dogs look up at my window to see where that damn noise is coming from? Youth is an overrated concept; a lot of people waste far too much of their lives trying to preserve it.

When I was a kid, I always wanted to be an adult. Now that I’m an adult, I wouldn’t go back for anything.

Being subtweeted by a mildly famous punk musician made me reconsider having labels for myself, for trying to slot myself in a series of neat little categories so people who don’t know me (and even people who do sometimes) can understand me. Growing up a black punk put me squarely on the outside of a lot of different piles of boxes. At some point, I realized being misunderstood comes as naturally for me as slipping on a pair of espadrilles.

Recently my sweet friend Anna asked me about earplugs and ways of breaking the habit of listening to music too loudly to prevent hearing loss. I replied to her, “Sweet Anna, I’m the last person you should be asking about good eardrum health.”

I’ve been on a campaign to make Toms the new punk rock shoe. I mean, come on, the Ramones wore Keds almost as often as they wore Chuck Taylors, and wearing Chucks is like walking on rubber dinner plates. Jessica Hopper, one of the most renowned music journalists on earth, proudly wears a shoe I used to sell to 90-year-olds when I worked in fashion retail. (They're the only ones who actually needed me to use the shoehorn I kept in my pocket.) So what if soccer moms wear Toms, too? So what if they were innovators in the world of “woke capitalism?”

I have five pairs (only two in similar colors) in various states of decay. I have a pair bought in 2014 with holes in the toes and black marks like I ran over them with a shopping cart that I only wear in the summer. I wore them (along with a way past overworn, pit-stained Li'l Sebastian t-shirt from 2011) last summer when I went to the Browns Point Salmon Bake for the first time since I was nineteen. Some of the soccer moms were wearing Toms, too.

I wore a pair of Toms the only time I’ve ever seen Jay Reatard live. Thee Oh Sees opened for them; this was the night I started proclaiming them as the best live band in the world. I had been a fairly recent convert to Blood Visions, Jay’s epochal, transgressive 2006 breakup record; rife with allusions to stalking, murder, deteriorating mental illness, and the longshot optimism that comes with trying to outrun your inner demons. I heard about the fist fights with fans, the usage of microphone stands as weapons, and getting kicked out of Gonerfest (a very tall order — more on that later — he famously quipped was like Hendrix being removed from Woodstock). I was witness to his immense, thunderous talent; I never understood the phrase “as skilled as the day is long” until I grew up and realized just how long the day could get.

Stories about Jay’s combative nature were becoming more and more scarce by the time I stepped into The Crocodile in June 2009. The floor was sticky with beer (already!) while I talked to Thee Oh Sees’ tour manager about an acquaintance we shared; I girl I once flew to Bloomington to see. It didn’t work out. C’est la vie. In the uncharacteristically humid space of the venue, I hung out with Larry Mizell Jr. and taught a stranger how to spell “blood” with her hands.

When the power trio went on, they were all playing these tightly-wound songs on Flying Vs and Jay’s energy was thrillingly confrontational (though not infamously so). The band punched their way through a set heavy on Blood Visions highlights and their excellent singles compilation released on Matador the year prior, with people flinging half-drank cans of beer and emptying their contents in the space above everyone’s heads. I saw the sweat fly and body heat scale toward the ceiling, I saw the blinding blue lights from the stage. Deep, electric blue as Jay whipped his mass of curly hair around. To finish the set, Jay stuck a microphone squarely into a bass speaker and happily summoned a torrent of ear-splitting feedback.

I heard a can crunch every time I took a step on my way out of The Crocodile that night. My Toms air dried on the patio for the subsequent three days.

These white women were from every part of the circles Que Linda ran with; some were aspiring fashion designers like her, others toiled away in bands, trying whatever talent, hustle, and subterfuge they could to get the A-side of their seven-inch single played on KAOS.

(She told me these stories around the time I began writing impressionistic short-form memoir pieces on my Tumblr and listening to a lot of Hüsker Dü and and Mission of Burma. As her tattooed hands shuffled a deck of cards and we sat at her kitchen table together, she looked me in the eye as she spoke. “Some people dismiss them as glorified diary entries, and that’s fine. Some people say it’s just stream-of-consciousness musings and they say you’re pretentious for considering yourself an artist, and that’s fine. But I really think you have something here. You’re good at telling your own story. You are a damn good writer in so many respects, but the beauty of your writing is so profound when you write about your life. People are going to connect with that.”)

Throughout our friendship, we had very involved discussions about her time in Olympia and how a decent portion of the second-wave riot grrrls she attended shows among excluded her from their reindeer games for being brown. Some of them were polite and pretended they weren’t doing what they were doing, others were brusque and made it clear through their actions (and their words in extremely coded language) that their groups were White Girls Only.

There were no violent altercations, though she expressed no surprise when I told her a few skirmishes were narrowly avoided in my years in basements and DIY venues and punk houses and even above-board, honest-to-god rock clubs with licenses and everything, because some asshole felt a black person shouldn’t be allowed to have a good time at a punk rock show. Nobody shoulder-checked her on the way to the bathroom, or loudly made a passive aggressive comment about her skin tone, or faked politeness in their astonishment that a woman of Dominican heritage identified as a punk rocker and walked the walk even better than she could talk the talk.

Simply put, these women were all afraid of Que Linda.

Somewhere, at this very second, there is a very handsome and very talented young man claiming to be an outcast, a misfit, even though everybody in school knows who he is and most people like him.

Even though by the time “Maps” jumped on every store playlist at the mall and Yeah Yeah Yeahs seemed destined to be far more than “that one punk band with the singer who wears crazy outfits,” they were a big group in my discovering the revelation that danger can be sexy; three years before they played an acoustic version of their hit song and made my eyes well up with tears thinking about someone who I loved in the moment, who had recently left my life and I only describe at 35 as a person with whom I’d had the best sex of my twenties with; around the summer I stayed with a friend’s parents and alternately watched porn and blasted this album throughout the wooden corners of their house when they weren’t home; when I saw them on the cover in SPIN — ripped up fishnets and a spacey blue top and makeup that would get somebody fired from a MAC counter, brilliant guitarist Nick Zinner in his war uniform of black oxford and black pants — immediately intrigued me about this cool band from New York when New York was still a little dangerous and not a concrete and glass advertisement for avocado toast; three years after my cousin’s friend and I were sitting on a park bench somewhere in public housing in the Bronx and someone he knew threw a 40 oz. bottle at us “just because” and we shrugged it off because this is New York; I wore three-quarter length sleeve baseball tees in damn near every color you could find in a standard box of Crayola (with one or two selections from my growing collection of punk band buttons) and Levi’s 511 skinny-fit jeans before narrow legged jeans for men could be found damn near everywhere pants are sold except Bass Pro Shops; by the time “Maps” jumped on every store playlist at the mall and “Who is Angus Andrew (of Liars)?” gets filed into Jeopardy Answers of the Future, I was already getting blank stares at punk venues for being the only black dude there.

Right before Ex-Cult played underneath Cooper-Young Gazebo, my friend Evan, a multi-year Gonerfest veteran, took me on my first holy pilgrimage to the shelves and shelves and shelves of gold at Goner Records where we were given lime green swag bags and I bought the Reatards’ Teenage Hate and Nots’ self-titled debut LP, because when in Memphis... [I might have bought a Gories live record, too] and he chatted with a well-traveled musician (and former member of Vivian Girls) named Fiona. I rustled with my heavier Burger Records vinyl tote (the one with the mod girl with a burger head). Evan and I were standing around wasting time when Ty Segall, just sitting down, chilling about fifteen paces ahead of me, took a good look at the shirt I was wearing. (It was Cassius Clay as rendered by Jean-Michel Basquiat.)

When the band played "Your Mask," easily the highlight of their Cigarette Machine EP, someone held a very small child wearing noise-cancelling headphones like the Baby Simba right in front of the band. I caught a glint of a smile amidst all the sneering.

I missed the Gonerfest a couple years prior when the Gories were a headlining act; I watched A Band Called Death when it came out and pondered how awesome an experience it must be for Mick Collins to sit in front of a camera and talk about how cool he thinks you are.

Pookie and the Poodles were riotously funny. Someone flung an empty beer can at Nots’ drum kit and drummer Charlotte Wilson didn’t even flinch. I told them they were my favorite band when I bought a pale pink Nots t-shirt which fit very tightly after their set (along with a copy of their “Hail Mary” seven-inch). A couple members of the band smiled at me as I proudly wore it the next night. Aquarian Blood was one of the most surprising experiences for me ever seeing a band (they managed to make a coach’s whistle a profound musical element in their songs). Nobunny is always a gas. Timmy Vulgar set off a green smoke bomb, its content hissing into the air as everybody jumped into each other and danced and flung beer like it was just another thing.

I joked about how that performance climax would get a guitarist kicked out of most Seattle venues.

During a rare Ty Rex set, Ty Segall and Emily Rose Epstein smashed guitars filled with glitter onto the stage. I found glitter in my Toms, my pants, my undershirts and underwear for the next two months. I found glitter in my bed. I saw flecks of glitter on my dirty carpet for at least eight months.

Obviously I don’t want to give too much away, but two of the book’s four protagonists are in a punk band together, described by many in the novel's environs as “experimental twee punk.” (It came from an idea that I thought would be cool for a band, something I’ve never heard before. I hear it in my head so clearly. The Velvet Underground, Talulah Gosh, Zadie Smith, and Sonic Youth are big influences on this fictional band.) They are on the bizarrely successful end of a career most artists dream and aspire to but usually only attain in their imaginations. (There are many factors to this, most of them have to do with the music.) They are part of a worldwide, tightly knit collective of punk bands whose local scenes had ostracized them for being “too weird” or “not big partiers” or some other completely arbitrary means of disqualification. They own a sprinter van and their own studio and have a violist who worships at the altar of John Cale.

The book itself, among other things, is extremely character-driven. Moments are built around both pivotal and completely made up punk rock bands. I've spent a decade trying to create a writing style that is individual to me, and when I began writing it in 2011, it was the moment where I begun to find my voice.

I have an immensely talented friend who is publishing her debut novel this summer; years ago we were rhapsodizing the long road to get to where we were and she described us as “punk writers.” I believe strongly in the concept of the literary underground; the outcasts and weirdos and community college dropouts barely anyone has heard of, crafting astounding, spiritually fulfilling, beautiful work. It encourages me to keep doing what I do, even if I have to shrug through my days in a stoned fog at a suburban supermarket, flirting with soccer moms and being pelted with the very worst questions about what I do.

“How’s the writing going?” “You’re still writing, correct?” I mean, no fault of theirs, but it’s like they think this is a cute hobby I chose, like writing didn’t choose me. I cast my heart to all the punks who spend their nights walking on floors slick with sweat and spit, and their days withstanding mundane questions about their creatively fulfilling other life being downplayed because they still have to work in offices and restaurants and fashion retail and supermarkets.

I’ve yet to finish this book for reasons that have accumulated and mutated and have all but completely disappeared: working through trauma catching up to me, lingering depression from losing my parents, the paralyzing fear of putting my all into this and falling on my face, spending my twenties utilizing my gift for self-sabotage instead of my way with words. I still feel doubt sometimes, but I’m confident in what I can do. So after four years, I’m slowly starting to work on it again.

As yet another great thinker I have for a friend once told me, “Doubt is part of the process.”

Someone told me they thought I was punk because I didn’t care enough about the rules to learn them. Another told me my writing sometimes reminds them of the best punk music; artistically uncompromising, rubbed raw down to the white meat, like the words I write when I’m angry are being screamed or barked. They told me they could tell when I wrote from the pit of my stomach. Perhaps both of those things are true, and in my best moments, I try to use them to my advantage instead of dulling my light for dull people or trying to accomodate people who just want me to be a spitting image of what they want me to be, what they want my art to be.

I recently gave my leather jacket to my 18-year-old co-worker at the supermarket. Am I not a punk because I wear cardigans and pro wrestling t-shirts when the weather is nice? Someone once told me I’m not a punk because the bulk of my work is “too gorgeous.” Am I not a punk because I don’t use many ugly words? There are enough ugly images in my mind to last me a lifetime. I believe beautiful words can create punk-influenced screeds. As long as people believe in the spirit of something, and can feel the scraping metal in their soul, they can use any approach to bring out the essence of the form.

Punk is is rooted in the act of destroying something, sure, but after the glowing embers, we rebuild a landscape in the image of what you want to see in the world. You know it when you hear it, you know it when you read it, you know it when you feel it rattling your fucking bones.