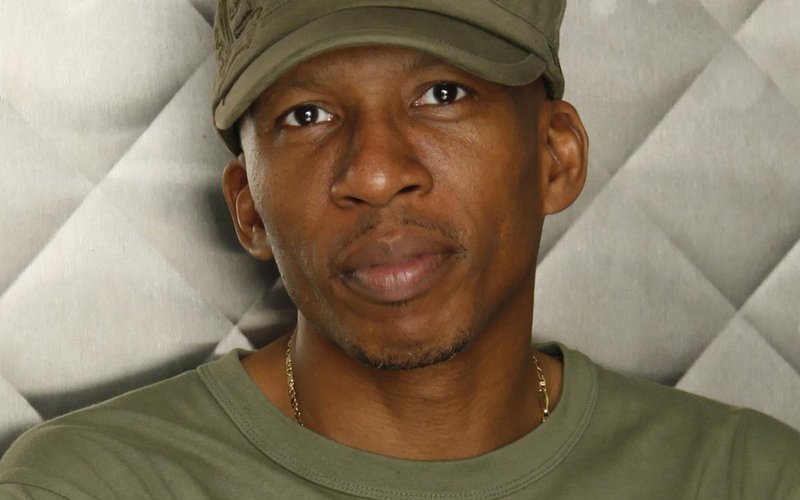

It wasn’t just the grand power of Chuck D’s voice and Flavor Flav’s charisma that helped establish Public Enemy’s It Takes A Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back an instant classic upon arrival. You can’t talk about the record without digging into the sonic wizardy of producer Hank Shocklee and The Bomb Squad. KEXP had the chance to chat with Shocklee about the creation of the album for its 30th anniversary, covering everything from their use of sampling to carving out a space for themselves in a music industry that had other priorities. Stream the interview in its entirety and read some selected quotes from the conversation below.

”The one thing about us making these records, we never made these records in any chronological order. They were just made. We were just making records all the time. And "Don't Believe The Hype" was a song that was made that I wasn't feeling and none of us was really feeling that record. It took for DMC to kind of like play the record out of the back of his Jeep at the time that the Apollo was letting out for their amateur nights. There will be like 3,000 people out in front of the Apollo Theater. And he had his car that had a huge sound system and he played that song at around 2:00 in the morning and then my phone started lighting up around 2:30 and I'm all like, "Well, what's going on?" They're just blasting, telling me, "Yo, "Don't Believe The Hype," everybody was going crazy over when they heard it coming out of the theater. And that's when we realized that that record – the demo at that point – was good enough for us to finish it off. And that could become a record.”

“The beautiful thing about Public Enemy was the fact that it was the anti-thesis. This is the record that no one expected. It's the record that no one had on their radar. It's the record that no radio station really played. It was all fostered through underground activity. So it was it was purely organic, purely underground, purely alternative. And even the approach to making it was purely organic and alternative. So therefore if you look at "Bring The Noise," for example, it didn't get no daytime play. It got purely nighttime play or purely alternative play at colleges and universities that had radio stations. So this is what made us big in that circuit, because we had to speak to our audience and our audience wasn't at the major radio station.”

From the start, I've always been an avid listener of music that had a message. So I've never really listened to a lot of records that was, to me, considered to be nonsense records that really didn't have any global or bigger message. Even if it was introspective, I was interested in it. So like when you're listening to groups like Sly and The Family Stone and Bob Marley and The Wailers and you're listening to Gil Scott Heron, you're listening to Marvin Gaye, you're listening to Stevie Wonder; those are records that were more than just records – they were soundtracks of our lives. They were also statements of social issues and concerns. And so I fell in love with this music called hip hop because I was always interested in cutting edge music. I just kind of like saw the emergence of street music and it was teen oriented. I saw that as analogous to the Berry Gordy "The Sound of Young A merica," if you want to look at it from that perspective. So for me, that was a big thing to see this new wave of music fans that was obsessed over this music called hip hop.

The reason why "Rebel [Without A Pause]" was very difficult to make and angst over it because we had did that record at Chung King studios with the late great engineer Steve Ett. The sax was in the same frequency range of Chuck's vocal. So the fight was, if I turn up the sax I get more aggression. If I turn Chuck up, I get more laid back. I need to get the message of Chuck across, but I needed the aggression of the sax to kick through.

“Everybody has a soundtrack in their head. When you talk to Chuck he's going to have a soundtrack in his head. If you talk to Flav, he's got a soundtrack in his head. But for me, it was a combination of things because when I'm looking at music, I'm looking at music not in terms of what one particular song gives me but what many songs have in common. So I would have to say that yeah this is Rastaman Vibration. This is just got Gil-Scot Heron's Winter in America. It's also Sly and The Family Stone's There's A Riot Going On. It's also Pink Floyd'd The Wall. It's so many records and pieces that's woven in to each other in order to make that statement. And keep in mind, that statement had to be made without melodies, without real instruments. And I think that that's on of its appeals. It was one of the first records that was made strictly from other records.”

“You know most rap records at the time were about 107 beats-per-minute, 108. We pushed "Bring The Noise" to about 109, almost 110. But not only did we push the tempo, but we also pushed the energy as well. So now instead of the samples being long, maybe two bars or four bar loop phrases, they are more like 16th notes. They were eighth notes. So the samples were coming faster. And it gave the impact of the energy being higher and higher and higher. This is what we were going for. We was going for a pure adrenaline.”

"What made James Brown great was his screams. James Brown was the only artist that was pushing you with the scream, using the scream as an instrument. Everything that P.E. is doing is paying homage to the scream that James Brown used. But we didn't use a human voice scream. We tried to find other sounds that would replicate that. So when you listen to "Rebel Without a Pause," you're listening to James Brown screaming."

"You have to understand, at the time, the dance music scene and the R&B/music scene, they were very much interested in upwardly mobile music. So it was music for the bourgeois. It was music for the people that were going to clubs. It was people that could get into the exclusive clubs, but it didn't necessarily represent what was happening, in my experience, growing up in the street. We had a totally different flow and a different feel. We wasn't accepted into those clubs. We couldn't get into those clubs. So we were kind of left out of the music scene as it was. It represented nothing of the struggle, nothing of the plight, nothing of the stuff that we had to go through to try to get into this business."

"It started from Yo! Bum Rush The Show, the first album. And I look at the albums as a trilogy. It started with Yo! Bum Rush The Show and then after we got into the business, It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back. And now, since we are now known and everyone knows we are, now you oughta be fearful of a Black Planet. So that whole set right there is reminiscent of our struggle and our beginnings from getting into the business and what we had to do to make an impact in the business."

”It's funny because Beastie Boys were very influential and bridging the gap. If you look at Def Jam at that time, you had L.L. Cool J and then you by affiliation Run DMC – which to me, L.L. Cool J was like the junior of Run DMC in terms of style and music. But then you had the Beastie Boys on the other end of the spectrum of Run DMC. They were more punk in their approach, but they happened to become rappers. Public Enemy, to me, was the bridge between the two. That's why we we held a dear place for both of them because we respected both of their visions, both Run, both L, and Beasties.”

”Sampling was an art form at that point. Everybody would sample, but they would sample maybe a kick a snare or maybe just a loop of a phrase. That was the most that sampling was. But for me, it was more about, "OK if we were a band, you would have different instruments." And so each sample represents a different instrument being played. So this album was coming from a band's perspective but strictly made from records that bands were playing on. It was like, "How do you take music that's been recorded to make music that's going to be recorded?”

You never know if anything is going to work until it actually gets to the people. Because to me, I've never looked at music from an elite perspective. I look I've always looked at music as a community thing. And P.E. wouldn't be anything without the fans and the community that accepted P.E. The people that got it, to me, are just as important as us making it.

For me, it's "Black Steel in the Hour of Chaos" because that record was like the start of something different. To me it was the birth of gangsta rap and it was sinister. It was a soundtrack that you can buy to.

The legendary MC was graciousness enough to talk through the mindset the group found themselves in while creating this masterwork. From drawing inspiration from his time working in radio and their aspirations to creating the hip-hop equivalent of Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On?, the incredible rhyme…

As we celebrate 6 Degrees of Chuck D, KEXP chats with the legend himself.

KEXP has announced the next in its series of album breakdowns - classic platinum-selling Public Enemy record It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back. On Thursday, June 21st, over the course of 12 hours, the station will play each and every recording sampled on the album, along with exclusive …