KEXP DJ John Richards speaks with Mike Simpson (a.k.a. E.Z. Mike) of The Dust Brothers about co-producing Beastie Boys' seminal second album, Paul's Boutique:

John Richards: So you’ve heard that we’re doing a 12-hour breakdown of the album. There are over 100 songs sampled, right?

Mike Simpson: Uh, that might be right. I’m not sure. No one was counting.

Well, we had to count them to check the timing and see if we could play them all, and it came out to nearly 10 or 11 hours of music. It’s a pretty amazing group of songs. Can you talk about the songs you used and where they were in yours and John’s lives?

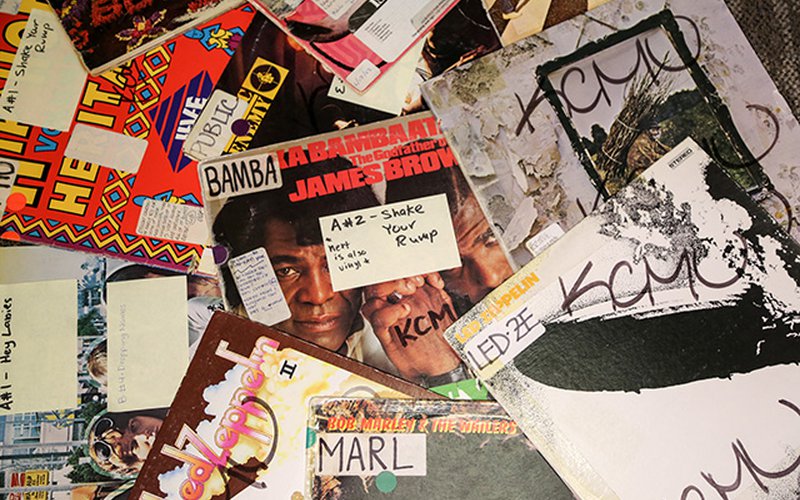

Well, I’d been collecting records since I was a preschooler, and at the time, I had maybe about 500 records in my collection. That was where all the sounds came from, was my experience collecting records throughout all those years. At that point, it wasn’t “all those years” though, seeing as I was in my early twenties. (laughs)

How many records do you think you have now?

Probably like 50,000 records.

Wow! So when you were putting the record together, from what John said, you guys were creating a Dust Brothers album and putting together these samples without the Beastie Boys in mind.

We had been constructing music beds to use as background music for promos for our radio show out in Claremont. Originally, that was the end result of what we were doing with these tracks. And then we connected with the guys that had just started Delicious Vinyl, who had just put out Young MC and Tone Loc. It was very similar to the Motown experience, because my understanding is that, at Motown, the songwriters would write songs and then the artists would come in. Each artist would take a crack at recording the songs and whoever ended up with the best version got to release that song. So that’s what we were: the Delicious Vinyl music factory. We would create these tracks and artists from Delicious Vinyl would take a crack at laying rap vocals over them. Whoever did the best rap would get to use the track on their album. And in the process of doing this, there were several tracks that had too much going on and didn’t seem to work for any of the Delicious Vinyl artists. Whenever we came across one of those tracks, we would set it aside and earmark it for the Dust Brothers album. When we met the Beastie Boys, they heard all of those earmarked tracks and their minds were blown. They asked what we were planning to do with the tracks and we said we were going to put together an instrumental album So they said, “No! We want to rap on this stuff!” So that’s how it all came together.

Did the Beasties change what they were doing once they heard your songs? How much came from their original writing?

Well, my understanding is that, at the time, the Beastie Boys had officially broken up as a group. They were in contract dispute with Def Jam and my understanding was the only way they could get out of that contract was to break up as a band. As far as I know, they had no intention of making another record. Licensed to Ill was going to be it for the Beastie Boys. Adam Horovitz was in LA filming the movie Lost Angels - they were not working on a record at all - and he’d gotten the film production company to fly Mike D and MCA out just to keep him company. So they were just hanging out with Adam and looking for a party. And we were hanging out with Matt Dike, who was one of the owners of Delicious Vinyl, but also a renowned DJ and club promoter in LA. The Beastie Boys had performed at one of Matt’s clubs when they were opening for Madonna, back in the day, so they knew that he knew where the party was at. And one day, Mike D came by Matt’s apartment just trying to find out where the party was. It was just good timing and good fortune that Mike D walked in while we were putting together some of these tracks and perked up his ears and asked what we were working on. My understanding is that our tracks are what inspired the Beasties to figure out their legal situation and pursue making another record with us.

How much do you believe that things are supposed to happen for a reason? I mean, everything had to line up there.

Oh absolutely. (laughs) My mantra for the record business has always been that it’s 10% talent and 90% luck and timing. And that’s totally true here. The Beasties were one of my favorite groups. As a radio DJ, we used to get promo copies of new artists, so we would get all the early singles from the Beasties and we’d play their songs on our radio show. And I remember the day Licensed to Ill came out. I sat in my bedroom studying the album cover as I listened to the record over and over again and was just blown away. I was also a little bit sad, because I was moved by my mom in 1978 from NYC to LA, and had I stayed in NYC, I would have probably met the Beasties in high school and would have lived out this fantasy that I would have been one of the Beastie Boys because we were all so like minded. (laughs) So the opportunity to work with them was like a mind-blowing dream come true. Like I said, when Licensed To Ill came out, I was just blown away.

I remember getting it on cassette and pulling out that plane in the artwork. I remember having to keep it away from my mom because...

Isn’t that crazy that the release of Licensed To Ill was one of those “where were you when it happened?” moments for the fans. It’s like tantamount to the moon landing or something.

The other thing is that seeing “Fight for Your Right (to Party)” on MTV was like the gateway for people like me in the suburbs of Eastern Washington. You saw it and thought, “this song is so goofy and campy and fun,” and it sucked me in to get it from the Columbia Tape Club or wherever I got it. And then I started digging into the album and I didn’t know what to make of it. I was so excited and so blown away that there was more depth to it than just that song. I remember thinking, “this isn’t the ‘Fight For Your Right’ band, this is something totally different.”

Yeah!

And I’m sure you were discovering the same thing with your radio show. Since we’re both radio people, I loved hearing John’s take on the radio show and you guys’ “eff it” attitude with FCC rules and music on the air that no one else would play at the time. Do you have some memories of that show and the impact it had on you?

Absolutely. When I moved to LA in ‘78, there wasn’t any rap music in California yet. when I got to Claremont College in ‘82, there was a little bit. Only a few people knew about rap music, but not many, so one night when I was DJing a party at Claremont, the station manager from KSPC came up to me and said, “This is really interesting music. I’ve never heard it before. Would you be interested in doing a radio show?” And I said yes, absolutely. So I went down to the station and they showed me how it all worked and said I’d be on Wednesday nights at midnight. It wasn’t a great slot, but I was lucky to be offered a show as a freshman, so I took it. The response was instantaneous. There was a large black community in Pomona - not so much at the colleges, I don’t think the show was popular on campus - but the station had a very powerful transmitter, and on a good day when the conditions were right, our station would go from San Diego all the way up to Santa Barbara. So I had callers from most of Southern California. People were really excited because there was no other place they could hear rap music. It was just a really great time in the history of music, and a great time to be getting involved in rap music.

It must have blown you away to have gotten calls from so far away from people who may not have ever heard that kind of music. It must have been great to hear them have that moment of discovery with you.

(laughs) There were less of those calls. Those calls were mostly from people who were familiar with the radio station and were not happy to hear it. (laughs) It was an alternative music station then – and at the time “alternative music” meant that it sounded like you were stuck between two radio stations – so it was mostly noise and ambient noise that was programmed for the station. They also had a very popular polka show. (laughs) The polka show was actually the highest rated show on the station until my show took off.

Now there’s an idea for KEXP. We don’t have a polka show. (both laugh) I love those stories and it totally ties into what we’re doing on Friday. Originally, we’d broken down an LCD Soundsystem song that took four hours to play all the songs referenced in it, What’s interesting is that while we’re celebrating the album, we’re also really celebrating the music that you and John listened to and owned and as we’re tracking all of it down - trust me, we don’t have all of it yet - as we dig into our 40 year-old vinyl library, It’s really a celebration of owning a record collection. I’m just curious as to what you think about us trying to pull this off.

I love that some people still think that this record is relevant. My goal as a producer is to make timeless music. I grew up listening mostly to black music: the Jackson 5, Stevie Wonder, P Funk, the Commodores, Gladys Knight, Ohio Players. But one of my biggest influences was the Beatles, who my mom listened to while I was growing up. I always felt that, from a construction point of view, the way the Beatles made records was so fascinating because they took all these different sounds and things people had never heard before and made timeless music. As a producer, to do the same thing was always my goal. The fact that, some twenty years later, people still care about Paul’s Boutique means that I succeeded. And I’m really happy about that. You know, there are websites dedicated to the samples we used and some of them are correct and some of them are incorrect, but at this point, I don’t even remember what was what. People say, “I love how you used this song at this point,” and I say “Oh yeah, I guess we did”.

It’s like people going up to Harrison Ford and knowing more about his movies that he does.

Exactly.

So as a station that’s been playing the album since it came out - to this day, it’s still highly requested - I’m curious as to what the Beasties themselves think about the album all these years later. When I was talking to John, it sounded like they didn’t want a hit, but you guys were looking for at least one single.

(pauses) You know, I have no idea. Of the three of them, I was the closest with Yauch, and while I enjoyed hanging out with those guys, Yauch was the one who spent the most time with us in the studio. (pauses again) I don’t really know what those guys think, so I don’t really know how to answer that question. Sorry.

Thinking back to the time though, can you tell me what MCA thought this album was going to be?

Well, I think that they really wanted to be born again. They weren’t crazy about “Fight For Your Right (to Party)” and the popularity that ensued, because it wasn’t really what they were about. At that point they really wanted to be a rap group. And while “Fight For Your Right (to Party)” is kinda a rap song, it’s not really a rap song. So I think that they were focused on not being a one hit wonder and breaking away from the popularity and the fanbase that the song had garnered for them. They really wanted to reinvent themselves and make a statement that they were more than “Fight For Your Right (to Party)”. In that regard, I think they would be very happy with the outcome of the record. One of their mandates for Capitol Records was that there was no promotion. They wouldn’t do any interviews. There was no marketing department involvement in the record. They really wanted to make a record that people would hear about from word of mouth. They wanted to surprise people and show people that they were more than this one hit wonder pop rap band.

Knowing that, what was your reaction when it came out? It wasn’t a really popular record when it first dropped.

Well, yeah. I was disappointed. I was so proud of the record and felt that, if it had been marketed, then people would have been exposed to it early on. Especially coming off of Tone Loc and Young MC. Even though the album didn’t have a bubblegum single, I still felt that it was along the same lines as those records in terms of production style and how interesting it was. So I felt like it should have met a bigger audience.

During that time in your life, you have this group you love and you’re working on this amazing record. Is there a story or a memory you have from that period that isn’t out there?

Just that when we weren’t in the studio, the antics involved were always high-level. Those guys were major pranksters. They liked to have a good time and they liked to be silly. Many of those stories have been reported before, but one of my favorites is the genesis of the song “Egg Man”. Before they rented a house in LA, they had all been staying at the Mondrian hotel while we were recording. And the Comedy Store was right across the street from that hotel. One afternoon, there was a line of tourists standing outside the Comedy Store, so the guys decided to get several dozen eggs and start pelting from the eight-story hotel. One family pulled up in front of the Comedy Store, and the dad got out to open the door for his kids when Yauch just threw an egg and hit the guy right in the head. The egg exploded all over him and his kids, so they just got back in the car and drove away. (laughs) Now, as an adult, I feel really bad for the guy, but as a 23 year-old, it was pretty funny, and it inspired the song “Egg Man”. Yauch took it so far as to hire toy designers from Mattel to come up with prototypes for the Beastie Boys Egg Gun. Somewhere in the world, there are these amazing renderings of these potential egg guns with the Beastie Boys brand on it. which is hilarious.

Man, I wish that those had been made. Another prank related question: how many phone calls did you get about joining the EZ Mike Fan Club?

Oh my god. (laughs) My phone rang off the hook for years. It took them a long time to take my phone number off the video.

So what were your first calls like?

Most of them were drunk college kids saying, “Hey man, I love you!” But there were also hardcore fans who would make very polite calls saying the record changed their lives. One time, I got a call from some girl who said her brother said to call this number, but soon she realized she’d been pranked by her brother. The funny thing is that we ended up going out on a date. She didn’t even know who the Beasties were at the time. We met at Monty’s steakhouse in Westwood, which was like a total Fast Times at Ridgemont high type story.

You guys went on to produce a lot of records. Beck, the scores for Fight Club and Muppets in Space - it’s all quite diverse. Where does this album stand for you in your discography? Would you go back to it at all when you were doing other those records?

Two records stand out to me as my crowning achievements and proudest moments. One is Paul’s Boutique and the other is the Fight Club score. The Beasties record was such a unique situation because those songs had been created to be a Dust Brothers record. I would say 70% of that record was made from ideas we made before meeting the Beasties. In essence, that music was made without an agenda. The other records, the Rolling Stones or Hansen, had an agenda. That was work for hire. Someone came in and said, “make this kind of music for me.” In those cases, everything I did was to serve the client. For Paul’s Boutique, that music came from my heart. That was the most natural and genuine expression of my own creativity. Fight Club was very similar. Even though it was guided by the film, David Fincher was not hanging over our shoulders telling us what to do. He basically said, “Did you see The Graduate?” And I said, “Yeah.” And he said, “You know how great the music is in that movie?” And I said, “Yeah.” And Fincher says, “I want the music for Fight Club to be that great.” And that was the only direction I got from him. So that project was another project that was just a pure expression of my creativity without someone telling me what to do. In that sense, Paul’s Boutique was so great. While I loved working with other artists, and I loved those experiences, it was just me making music for somebody else.

Sometimes there are stories about albums that are full of misperceptions, but this feels like a really pure story. It happened on the coast you didn’t think it would happen on, and even you moving out to the other coast seemed to work out for you on this album.

Exactly. I have to say, Beck’s Odelay was a similar experience. Beck had just come off of “Loser” and everyone wrote him off as a one hit wonder. I think Geffen Records even thought that and didn’t expect him to have much of a future with them. So when we met Beck, it was like kids messing around in a playground playing with popsicle sticks or whatever to create something cool with no agenda. The difference being that most of Paul’s Boutique was created before, whereas with Beck, we knew we were working with Beck. I think part of the success of Odelay is the same as Paul’s Boutique because we made those records in a vacuum. I guess with the Beastie Boys, there were expectations for a second record because of the success of the first, but there was still no record label guy telling us what to do. We just got to play and have fun, and I think that’s sort of the key. That became a lightbulb moment for me. Learning that the records I had the most fun making were also the most successful. There’s a direct correlation to your state of mind and your emotions while you’re making the record and the final output.

And these aren’t just albums you love, but albums that millions of people love. I think there’s a lesson there, whether you’re a fan or an artist.

Oh yeah. It’s such a crazy business. It’s so unpredictable. Like I said, it’s 90% luck and timing, but if you don’t have fun with it, people will be able to tell.