With Rewind, KEXP digs out beloved albums, giving them another look on the anniversary of its release. As the album turns 35 years old this year, KEXP's Dusty Henry revisits this classic record from the underground cellist experimentalist icon and finds greater understanding for his work at large.

Throughout his tragically short time with us, Arthur Russell lived numerous musical lives. And most of those lives wouldn’t be heard until long after he was gone. A cellist, composer, experimentalist, disco dance-floor diviner, folk-country balladeer, avant-garde art rocker, self-imagined pop star, and infinite other combinations of genre and superlatives – what’s most remarkable about Russell is how he often would exist as all of these things at once.

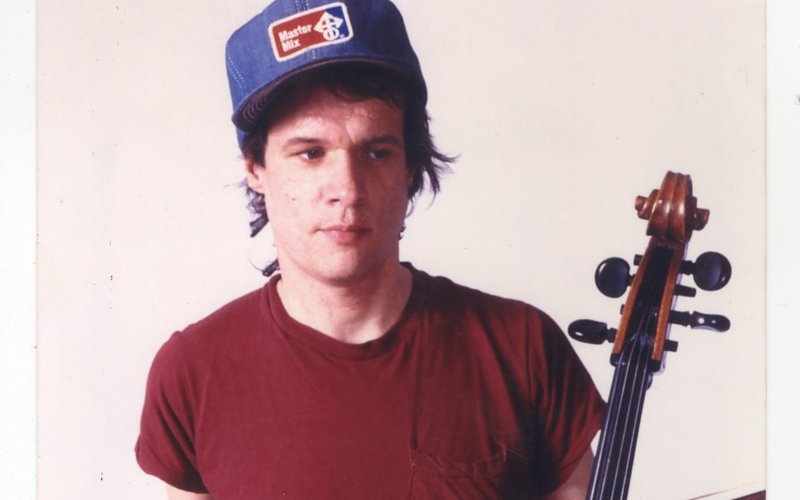

Before we get further, I feel it’s important to disclose that I have only come to really immerse myself and fall in love with Russell’s music in the last year or so. So, I cannot claim to be an authority. But that, too, speaks to the legacy of Russell, an artist whose work has flourished and perpetually rediscovered after his lifetime. A Van Gogh-like figure in a trucker hat.

Born Charles Arthur Russell, Jr. in 1951, Russell spent his early years in his hometown of Oskaloosa, Iowa, whose cornfields and rural living would be a constant source of inspiration for the songwriter long after he’d left. At 18, he’d leave for San Francisco and immersed himself in the progressive artistic community. He’d take up his childhood instrument of the cello and perform it alongside chants in a Buddhist commune, solidifying a meditative center that would live throughout his music for years to come. In San Francisco, he’d also meet esteemed poet and writer Allen Ginsberg, a lifelong friend, collaborator, and, at one point, a brief romantic partner. When they both moved to New York, Ginsberg would provide Russell electricity to his East Village Apartment through an extension cord.

New York brought Russell too many notable connections and foundations to list. He’d work with the likes of David Byrne and Talking Heads (contributing cello to a tremendous alternate version of “Psycho Killer”). He’d take up a curatorial residency at minimalist art space The Kitchen where he’d boldly book The Modern Lovers. He’d frequent disco clubs and create numerous dance aliases like Dinosaur L and the Indian Ocean and had a minor disco hit with Dinosaur’s “Kiss Me Again.” Crucially, he’d fall in love with Tom Lee who would stay with Russell throughout his life and now operates as the executor of Russell’s estate.

I do not have enough space to go into every detail of Russell’s life – details which have been remarkably preserved in the documentary Wild Combination: A Portrait of Arthur Russell and Tim Lawrence’s book Hold On to Your Dreams: Arthur Russell and the Downtown Music Scene, 1973-1992. But the point being, Russell did a tremendous amount of things in his life, yet little of that work made it out of his infamous and vast collection of home-recorded tapes. Russell was a perfectionist, a trait that’s not necessarily good nor bad, but meant he was self-critical to the point of putting out very little music. His only proper album released before his death in 1992 came with 1986’s World of Echo.

That Russell was so particular yet deemed World of Echo fit for release is fascinating for numerous reasons. Perhaps the biggest reason is that, on its surface, Echo is arguably some of the least accessible music on the spectrum of Russell’s as we’ve come to know it. In the time since his death, Audika Records have released brilliant compilations of material like Love Is Overtaking Me, Calling Out of Context, and Iowa Dream that all show bits of Russell’s experimental side but also boldly highlight his prowess as a singer-songwriter. Somehow World of Echo begins to feel like an anomaly.

World of Echo is a murmur of a record. Russell sits alone with just his voice and cello. The cello produces a murky sound, often soaked in echo, reverb, and distortion as the bow percussively saws across the strings. Russell’s voice feels restrained and quiet, his words mumbled and often indecipherable, oscillating like sine waves. It’s a record that sounds simultaneously like it was recorded underwater and in a large, empty gymnasium. The short opener “Tone Bone Kone” breaks in two drastically different movements within its one-minute run time, beginning as a shoegaze-cello ballad before abruptly transforming into a plucky sound experiment with the title’s words chanted. It may come across as an inauspicious start, or, at the very least, a strange introduction to Russell.

I can’t say if I liked World of Echo on my first listen. I certainly found it… interesting, if not perplexing. As I kept deep-diving into Russell’s work, Echo continued to allude me. Falling in love with his more traditional acoustic pop songs like “Oh Fernanda Why” and “Words of Love,” I thought that maybe this was just a part of his work I wouldn’t connect with. But as I was discovering the work of Laraaji around this time, another wunderkind musician who transformed ambient and new age music for himself and subsequently the world at large, Echo continued to gnaw at the back of my mind. What had Russell been trying to communicate? What was I missing here?

Surprisingly, it was Kanye West that first started to unravel the knot. As I was reading into the record, I saw noted that West’s “30 Hours” from The Life of Pablo sampled Russell's “Answers Me” – a factoid I somehow missed in Pablo’s frenzied promo and which felt obvious in retrospect. It’s a brilliant sample, somehow recontextualizing Russell’s words of “where the lions go” into “30 hours.”

Russell’s greatest skill was putting together seemingly incongruent musical ideas and proving they can work. Not only does that parallel West, but it’s put into practice on “30 Hours.” No one could speak for Russell and what he’d think of the sample, but it, at least, feels like a spiritual continuation of what we sought throughout his career. It also backed up Russell frequently insisting that he saw himself as a pop star and that World of Echo was a dance record at heart. Whereas Russell’s original record has no drums, suddenly I could hear what he meant.

World of Echo comes across as studious or dense, but like a “magic eye” illusion poster, it works when you don’t try so hard to figure it out. Pop music can be profound, often a boon by its simplicity and predictable structure – certainly no slight intended, the opposite even. When you stop trying to focus and find definition through the fog of a song like the sprawling “Soon-To-Be Innocent Fun/Let’s See,” Russell’s melody and cello reveal themselves to be quite catchy and especially lovely. The way his voice rises and falls is mesmerizing and endearing, even as slurred sentences start and end before they reach their conclusion. The mysterious and unverifiable lyrics do what great pop music does in letting the listener open up their imagination and interpreting how and what it means to them.

A song like “Being It” could be a pop-rock anthem with a monstrous drum kit pounding away in the background. But it could also a dancefloor rager. Or a tender, show-stopping ballad. Its amorphous nature allows it to be whatever it wants. The type of freedom I imagine many of us crave, or at least I can speak for myself, to be who we want. As Russell says in the song, “Being isn’t certain.” Ambiguity is something Russell revels in on the record. “The Name of the Next Song” finds him practically rewriting the song as he goes, periodically stopping his furious cello playing to speak a new song title into existence, ranging from “Anti-American,” “Take A Gander At That”, and “Dodo” among others across the track’s eight minutes.

And throughout all of the music, of course, is a walloping echo effect. Every strum, bow, pluck of the cello, and every note sung is doused in echo. The music reverberates out and back in on itself. It has the effect of making World of Echo truly feel like a self-contained place for himself, where he makes his own rules. It’s a solitary place, and there is a sense of loneliness that’s unspoken but felt throughout the record. The effects conjure this image of Russell alone at his cello, the walls bouncing the sound back to him as he fills the space with the music overflowing from him.

It’s easy to label Russell’s music as esoteric and experimental, as I was quick to do. And on some levels, it might be. But that was not Russell’s intention. To hear from his friends and collaborators, his fusion of genres and seemingly contradicting ideas were done in earnest pursuit of writing pop music. Looping cellos with disintegrating reverb were only the means by which he executed his heavenly melodies and musical visions.

This is something I think about a lot when I’m listening to experimental music, especially when I want to share it with others. There’s often a proclivity to assume it as navel-gazing or intentionally inaccessible, meant to drive others away – something to totally kill the vibe when you’re handed the aux cable. But I think Russell’s approach synthesizes to me the idea that we all hear and feel things differently. Further, there’s value in stretching ourselves to try and understand these other ways of feeling and in the process might even start to see mirrors of ourselves or our own ways of understanding. Music, after all, is poetic in nature.

As many great pop records do, World of Echo ends with a love song. “Our Last Night Together” is, in my opinion, one of Russell’s loveliest works and one of the clearest messages on a blurry album. Echoing himself, he periodically repeats two phrases: “It’s our last night together” and “Although you’re coming back.” Once again, seemingly contradicting thoughts that when put together work in wondrous ways.

In one of the verses, he sings, “Although you're coming back/I'm losing you for now/This job is just a one-way street/It's taken you away from me.” These words make me think of an echo. The words escaping your mouth and gone forever, but also returning back to you like a faint ghost in the echo that bounces back. There’s also possibly some self-awareness within this as well, Russell acknowledging his “job” of music taking him away from his partner, consuming himself in his own world of music when maybe he should be with his lover, sharing these fleeting moments. But really, it’s hard to prescribe any specific meaning. Russell’s magic is in how it speaks to you.

Russell passed away in 1992, one of the many gay men and women who lost their lives from AIDS. He would have been 70 this year. It’s inconceivable to imagine the voices, perspectives, and histories lost from this epidemic, stories we as a culture at large cannot get back. While Russell is not here with us, his voice continues to find its way back. More and more of his material continues to crop up thanks to the herculean efforts of Tom Lee and Audika Records. Somehow it still feels like Russell is talking to us through these continued reissues and rediscoveries. His work continues to find its way back, like a proverbial echo.

Before breaking up due to the pressures of their sudden explosion in popularity, the Olympia band created one of the most important punk releases in recent memory. Martin Douglas explores.

In honor of Pushing Boundaries, and in celebration of the album's 25th anniversary, KEXP's Janice Headley revisits Cibo Matto's genre-defying 1996 debut full-length Viva! La Woman.

Looking back at the new age opus and an underheard masterpiece that may give peace and perspective in our current moment.