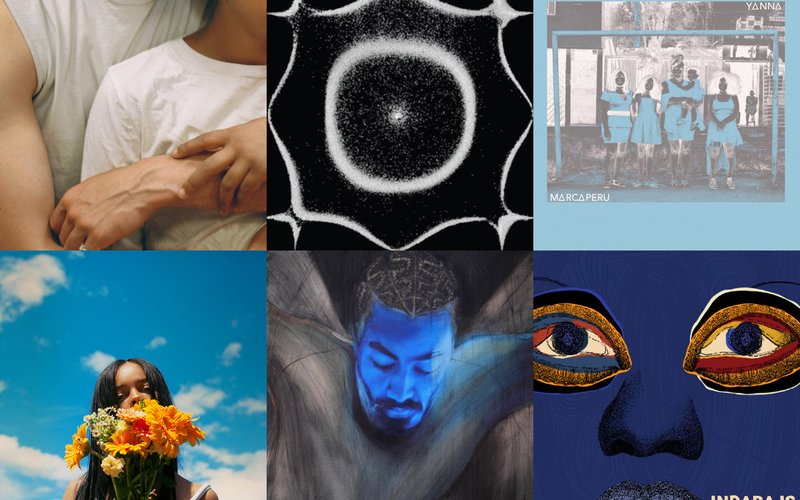

Each month with In Our Headphones, members of KEXP's Digital Content team share the music that's resonating with them right now. For this installment, in conjunction with Black History Is Now, the team shares reflections on music from modern Black artists in their personal rotations.

Navy Blue’s personal, emotional screeds — full of gorgeously written allusions to depression and ancestral weight — reminds me a great deal of the kind of writing I was doing on Tumblr a decade ago. I hadn’t found this side of me until my late-twenties, an advanced age compared to Navy and his peers Earl Sweatshirt, MIKE, and Mavi, but years prior to this strain of rap finding a widespread fanbase. Childhood trauma made me a late bloomer in many respects, but that weird microblogging platform was the blossom for me.

Though during those times I still carried said trauma I hadn’t yet processed on the backburner, though I was still running away from my past in a way that would reach its climax — or its nadir — during a suicidal summer when I was 29, I found myself feeling nostalgic about Tumblr the other day. Because while my depression and anxiety would remain unchecked (I would eventually be officially diagnosed with those and PTSD upon therapy when summer gave way to the browning leaves of autumn), I had the time of my life on the platform.

My soaring confidence, creative ambitions, and belief in my intellect flourished in a community of like-minded weirdos. Among other talents, like my gift for flirting and emotional connection which turned me into a Tumblr heartthrob of sorts, I found my creative awakening there, writing impressionistic, stream-of-consciousness memoirs in miniature; a way to finally heal from the terror of my childhood, but also my way of turning my love for words and stories into art. It’s safe to say I see a lot of myself in the writing of artists like Navy, Earl, and MIKE.

There is a maturity I wish I had in Song of Sage: Post Panic!. Sage Elsesser’s words are crafted to visualize the beauty in the scenes he drafts with an evocative, intuitive pen. Sitting around a big, wooden table with his family; Aunt Gerry’s chicken in the pan-frying. He grieves over his grandfather and brother, heeds the words of his father, and shows the youngsters in his life how to cherish their brown skin.

On his breakout release Àdá Irin, Navy guested Ka, the closest thing he has to a spiritual predecessor. On this, his sophomore full-length effort, he highlights collaborations with his peer Maxo, billy woods (the platonic ideal of a brainy, vivid, and radically minded rap writer) and one of hip-hop’s all-time greats, Yasiin Bey — on the loungey “Poderoso” and pensive “Breathe,” respectively. (Elsesser shouts out Ka, the bard of Brownsville, on the latter.) However, 14 of the album’s 18 tracks are driven by Navy’s soft-spoken voice, nimble flow, and utterly graceful writing.

Over jazzy guitar and soul music chopped into chunks, Elsesser unfurls a lifetime of depleted spiritual reserves and what it takes to refill them. It’s the type of rap music easiest for me to relate to after spending more than half my life bleeding ink into notebooks. If I could rap, I probably would be making music like this instead of punishing blank cursors with psychic strain and writing prose poems about new music and trying to pass it off as critical discourse.

Song of Sage: Post Panic! is an illuminating tapestry of meditations on self-harm, colonization and ancestral weight, gentrification, anxiety attacks, the grief we carry throughout our lives, and the ties that bind Black people together. Elsesser writes elegantly about new neighbors calling the cops on him, karma from a past life coming home to roost, cannabis flower as an antidepressant and trying to kick the habit, NFL greats from the late-nineties (the period from which he was born), and white people “hunting us for sport.” Bring that timeline forward about fifteen years and add well over a hundred pounds worth of indie rock records and you’d basically have my Tumblr timeline circa 2009-2012.

On one hand, I feel like the person I was always meant to become. On the other, I feel like I’ve been spending the past ten years trying to get that guy back. I have a patchy beard and weigh at least 30 pounds heavier now, but I don’t mind that. I miss the steady stream of electricity in my bones, the passion and energy to spend weeks on end thinking about nothing but creativity. Now I look at listings for houses with my girlfriend; I worry about when I’m going to be able to visit my 80-year-old grandmother who has served as the only constant in my life since birth; I fret over the state of the world and if there will be anything left behind for future generations.

Oh, to be in your twenties, discover your attractiveness and charm, and to only have to think about yourself. My life surely would have been better without all the hardships I was suppressing, but even so, my life was pretty motherfucking fun, and those years marked the beginning of the journey to find the person I am today. Navy Blue simultaneously reminds me of the person I was and the person I am, the people I came from, the brain cells I’ve lost from steaming vegetables, the words I lost to adulthood. — Martin Douglas

“A mi me cuidan mis amigas, no la policía” / "My friends take care of me, not the police"

This is the chorus from the new South American anthem of my life, “Marcaperú” that comes from San Martin de Porres, Peru, where the queer Afro-Peruvian rapper Yanna grew up. I believe that her music faces the raw reality of the systematic racism that the black community experiences in Peru and the femicidal territory that we inhabit in Latin America and the entire world. A territory that kills us with the complicity of governments and police officers, a “justice” that does not take care of us.

I am not going to avoid the fact that this reality overwhelms me and that the levels of violence that we, women the world over, live in means that last night I could not sleep after learning that another woman was murdered at the hands of the police. In this case her name was “Úrsula” and the country where this happened was Argentina, but the names appear hour by hour, spread throughout the continent. Then last night, biting my lips with hatred, I listened to “Marcaperú” over and over again.

As a black woman, LGBTQIA + activist, as an Afro-Peruvian and as an artist, Yanna denounces her personal experiences of discrimination with music in a way that makes you feel like she’s telling your story, too. She sings with an unforgettable, deep voice as she rails against the struggles that some minorities experience everyday.

Yanna only has three songs uploaded to her platforms “Marcaperú”, “La Vuelta”, and “Miau.” You can hear her musical roots taken from hip hop, reggae, trap, dancehall and Afro-Peruvian music.

With her new EP on the way, I am hopeful about her open future and the new music she will bring us. Yanna's voice is past, present and future. It’s also my musical connection with my amigas right now. — Albina Cabrera

After the heartbreaking news of MF DOOM’s death, my thoughts quickly turned to Madlib. I assume this was the case for others as well. The Metal-Faced villain and Beat Konducta became synonymous with one-another after their masterful collaboration Madvillainy in 2004. But more than that, both artists – alongside J Dilla – made-up an unofficial ‘holy trinity’ of producers who defined underground hip-hop as we know it and pushed sonic and creative boundaries. Now Madlib is the last man standing.

While this may sound grim, to me it serves as a reminder to appreciate this legendary artist who we still have with us. Since his days in Lootpack, Madlib has continued to push himself to new creative heights across various monikers – Madlib, Quasimoto, Yesterday’s New Quintet, and DJ Rels, to name a few. His recent collaborations with Freddie Gibbs, Piñata and Bandana, have brought along a new generation of fans. And with the emergence of “lo-fi hip-hop beats” as “a thing,” it’s heartwarming to see the originator of the sound get his due.

Sound Ancestors is billed as the first proper solo album under the Madlib moniker. There are no features and no collaborators aside from Kieran Hebden – aka Four Tet – who helped arrange and piece together the record from beats Madlib had sent him over the years. We’ve heard Madlib on his own remixing the Blue Note catalog and with his Quasimoto records, but Sound Ancestors puts the spotlight on Madlib as a producer with no constraints or pretext.

The record finds Madlib digging deep into his legendary record collection and gleefully indulging his whims and instincts. Lead single “Road of the Lonely Ones” mashes up two songs from ‘60s Philadelphia group The Ethics, reinvigorated by an impeccable drum loop. “Dirtknock” flips a track from Welsh post-punk outfit Young Marble Giants and turns it into a dank and brooding hip-hop groove.

The way Madlib works got me thinking – is Madlib actually a solo artist? I promise this isn’t just a hot take. It’s not because he often works with other collaborators or that he crosses over his many monikers. The records he samples feel like his collaborators. He doesn’t need to talk directly with the artist he samples to get to the emotional or spiritual root of a song. Madlib has a way of communing with the music on wax that is unparalleled outside of Dilla and DOOM. He doesn’t just listen to the music he’s sampling, he understands it and sees the potential of what else it could become. It’s not too dissimilar to a bandmate coming to practice with a loose idea of a new riff and the band building it out into something transcendent.

All of this makes me consider the notion of eternal life. Beyond heavenly realms or greener pastures, what happens in this physical world after our spirit leaves? Dilla and DOOM are no longer with us, but in some ways, it doesn’t feel like they’re gone. I can put on one of their records and hear their voices, feel their presence in the beats. Even music we’ve heard hundreds of times can reveal something new – a sample you never noticed, or maybe a feeling evoked that you hadn’t felt before. And that to me is the spirit of Sound Ancestors and Madlib’s work at large. He isn’t just sampling, he’s conversing with the records on tape. He’s finding new ways to keep this music alive, however obscure or not. Dead or alive, the artists’ work carries on and finds new ears in new ways – a sort of musical reincarnation that Madlib specializes in.

I know that Madlib won’t be here forever, you and I won’t be either. But whenever that day comes, we’ve all left some sort of impact that will have ripple effects. Few of us ever get to see these ripples for ourselves. It is a blessing to have Madlib with us to see his own influence imparted and to also continue digging and revealing the glorious works by artists some of us might have missed. Now is as good as time as any to celebrate Madlib. Throw on Sound Ancestors and hear the past reflected through Madlib’s presence. — Dusty Henry

One of the many things I’ve been missing this quarantine winter is wandering through museums. Living under modern capitalism, where even our attention is commodified, it’s refreshing to be in a space devoted to the slow, deliberate process of creation and observation. I find a similar sense of sanctuary listening to Duval Timothy’s 2020 release, Help. The album’s color palette is varied and unexpected, including gradients of warped recordings, splashes of found sounds and watery guitars, and the anchoring warm tones of acoustic piano. At times while listening, I get the feeling I’ve wandered into that room in the museum with an abstract video installation on loop. Maybe at one point I even tilt my head and wonder if I’m “getting it.” Like spending an afternoon in a museum, the joy of this music is in the exploration.

It comes as no surprise that Timothy finds outlets in more than just music, with his artistic practices including photography, textiles, painting and sculpture. He displays some of these around Help; he photographed the album cover and co-created the claymation video for “Slave,” making the record an immersive experience in his talents. Weaved throughout his body of work and central to his vision (and his brand, “Carrying Colour”) is the concept of color, especially as it relates to identity.

Duval Timothy is of mixed heritage and splits his time between London, UK and Freetown, Sierra Leone. His work, as an extension of his experience, breaks open the complexities of diasporic identity. The title of his 2018 album, 2 Sim, references slang for a mixed person who has a sim card for each country. Before that, 2017’s Sen Am sampled Whatsapp voice notes from friends and family in Sierra Leone.

On Help, we’re given more space to find meaning through abstraction. “Slave (feat. Twin Shadow)” loops, filters, and manipulates the word “slave” until its significance is questioned and ultimately broadened. A clip of Pharrell Williams lamenting the music industry’s exploitation of Black artists, in contractual terms that barely try to hide it, leads to the final climax of blurred repetition. The next track, “TDAGB,” features Timothy’s sister saying, “Things don’t always get better. It’s not just a matter of time until everything works out.” I hear this as a call to action, that unless disrupted, the systems that exploit and oppress will continue to do so.

But that’s one interpretation. Meditations like “Look,” where Timothy samples the painter Ellsworth Kelly quoting photographer Diane Arbus (a very meta moment), we’re told that “If you investigate enough, everything becomes abstract.” Starting from that place of abstraction gives us room to draw our own conclusions. — Isabel Khalili

I went to college in what we all referred to as the armpit of Southern California. East of L.A., Scripps and the other Claremont colleges sidle up against the San Gabriel Mountains, just far enough from the foothills that it could reach for but never fully find refuge in the shade of Mt. Baldy. It was hot, dry, and bright: perfect for a festival. Every year, campus emptied in April. The exodus led us inland; we traced the mountain range on our car windows until the brown land was speckled with wind turbines, and Coachella Valley finally cracked open before us against a lavender twilight.

Say what you will about Coachella, it’s one of the biggest festival productions in the world and the Claremonts were the closest colleges to Indio. And despite being a regular at pop punk moshes since my 13-year-old scene days, Coachella was the first festival I ever went to. Forget the crowds and the politics – it’s a music lover’s Disneyland, where I’ve seen everything from Beyonce’s Homecoming to a score-hopping marathon set from Hans Zimmer. More than anything, though, I’ve come to associate my festival memories with future bass, deep house, and chillstep. Future bass had a standout year in 2016 and since then I’ve stored my memories in Odesza’s soul-quenching music, the sublime catharsis of Flume’s live experimentation, the involuntary convulsion dancing that Elderbrook commands. From Disclosure and Tourist to Hayden James and Mura Masa, I prayed at the altar of artists who delivered me to euphoria through bass that buries itself in your body and blossoms from within, the slow builds and heavy drops so good they rival sex (I suppose the drugs help), and defibrillating BPM that makes you forget that it’s what stopped your heart in the first place.

The hallmark purveyors of electronic dance music in today’s mainstream festival circuit have a few things in common: first, they’re masterful collage artists who paint with a potent blend of sound and emotion that’s arguably more intoxicating than acrylic. Second, they’re mostly white and male.

EDM doesn’t just have its roots in Black history, it was a genre created to backtrack a safe and inclusive space for Black and Brown people, where those in the margins became the body paragraphs and they could move with complete freedom. The dance floor was a sacred space “for people who have fallen from grace,” Frankie Knuckles said. As the Godfather of House Music, he mixed disco, soul, rock, and rarities into an infectious and transcendent stream of musical consciousness at Chicago’s Warehouse. Larry Levan, friend to Knuckles, introduced the dub to dance music and developed the spiritual blueprint for the modern club with a decade-long tenure at New York’s Paradise Garage. These two pioneering pillars of house, both Black, carved out spaces for oneness through a unifying groove – and carved even deeper grooves in the musical consciousness of the underground community.

Not long after, Juan Atkins, Derrick May, and Kevin Saunderson carried the history forward with their development of techno in Detroit as The Belleville Three. Inspired by Kraftwerk, they used synths to capture Detroit’s industrial dystopia on the fertile ground Knuckles and Levan had sowed for electronic music. At the hands of The Three and others, the vision and aesthetics of techno were firmly grounded in Afrofuturism. Juan Atkins’ Model 500 moniker was a nod to the ideology’s sci-fi tradition, as was electronic duo Drexciya. Both Drexciya and Underground Resistance used album imagery and liner notes to develop futuristic mythos steeped in anti-colonial motifs, and depicted futures reclaimed by the African diaspora. In addition to being subversive protest music, electronic as we know it today was at its inception crafted to cherish, nurture, and protect Blackness.

Across the web of time, slick with appropriation and big label co-opting of subcultural custom, electronic dance music has been whitewashed to the point where you make mental notes of rare artists of color on major festival lineups. The world of anthemic, festival-ready EDM is particularly white and male-dominant, which is why TSHA stands out.

The self-taught producer dropped Flowers late last year, an EP that sounds familiar at first listen, until you realize that you haven’t heard this tight, resonant, emotionally-charged electronic before. “Sister” sets the tone for the four-track EP, establishing atmosphere with twinkling piano and buoyant strings. Over the four-and-a-half minutes, TSHA proves herself a master of voice to create texture, body, and catharsis. At times, she manipulates high-pitched vocals into wistful apparitions that refract light as they dance into the song; in other moments, she invites deeper vocals to blossom over the beat, perfectly balancing the track’s brighter elements. The effect: a chasm, both sonic and emotional, in which her own crystalline voice echoes through the divide singing words of hope and reunion.

This is perhaps a more auteuristic perspective than music writing allows (I’m new at this), but the chasm she carves with the vibe-setting “Sister” is the space in which the remaining three tracks shine. TSHA kicks up the urgency with “Renegade.” Guitar and synths root the track in a dynamic groove while vocalist Ell Murphy searches through the dizzying and dazzling instrumentation for “the sweetest sound.” Gabrielle Aplin joins TSHA on “Change,” where sharp pitch pivots and more subtle vocal manipulations perfectly compliment the acid-doused synths for a brilliantly paced, unacerbic track. On “Demba,” Malian group Trio Da Kali’s commanding chants are complemented by a booming house beat. The centerpiece of the final song is the griot group’s vocals, and TSHA brings West African oral history to the fore in a celebratory close of the EP.

In an all-too-fleeting 16 minutes, TSHA breezes through a myriad of electronic subgenres with seamless togetherness in a mark of bold personality and style. The air-tight EP channels the multi-faceted euphoria of festivals and with it, TSHA reclaims a musical birthright within a whitewashed lineage. There are few highs that match losing your body in a fit of pure expression to music, especially music designed to command your heart rate. And few can understand the value of corporeal freedom more than Black Americans. It’s not surprising that electronic dance music was created from and for the collective trauma endured by Black communities. TSHA revitalizes that history simply by creating the music she does. Her exultant bangers are primed for Main Stage and it’s only a matter of time before she takes the mainstream festival circuit. Until then, her music is an invitation to dance freely and uninhibited regardless of your makeup and melanin. — Tia Ho

It’s been a long time since a song made me literally stop in my tracks, but that’s just what happened the other night when my boyfriend, Joe, played this on his radio show, not once, but twice, because it’s just that captivating. Once I found out where to find it, I’ve played it maybe a hundred times more.

I’m not going to front like I know anything about South African music, but here’s what I learned about guitarist Sibusile Xaba. He hails from the KwaZulu Natal midlands, and with his music, he aims to uphold the traditions of Maskandi and Mbaqanga (two Zulu music genres). He doesn’t consider himself a performer, but a diviner, using music to heal, a philosophy shared by one of his influences, the late Dr. Philip Nchipi Tabane who led the band Malombo. Xaba was also mentored by Madala Kunene, known as the “King of Zulu Guitar,” and iconic Maskandi vocalist, Shaluza Max.

On this song, he’s joined by collaborators Fakazile Nkosi and Naftali on vocals, and producer AshK, who are all also members of the Pretoria-based artist collective CAR (Capital Arts Revolution), whose aim is to “rejuvenate artists through the teaching ideology of love and self-emancipation.”

“Umdali” showcases Xaba’s intricate finger-picking on acoustic guitar, sounding somewhat reminiscent of an Elliott Smith song with its hypnotic, melancholy tone. In a bizarrely harmonious contrast, AshK layers futuristic Stereolab-ish sound effects in the background, what sounds like droning synthesizers mixed with haunting wind noises and bird calls. (Is that a theremin towards the end?) Both Nkosi and Naftali contribute warm, expressive vocals to their parts, and while I have no idea what they’re saying, it’s absolutely gorgeous and somehow comforting? (I mean, Cocteau Twins are one of my favorite bands of all time, and I don’t always know what Liz Fraser is singing!)

The song can be found on the album Indaba Is, a compilation just released by London-based label Brownswood Recordings spotlighting current South African improvised music. Google tells me the word “indaba” apparently means “an important conference held by the izinDuna (principal men) of the Zulu and Xhosa peoples of South Africa,” and while I’m not crazy about the meeting being held by just men, it does make a fitting title for this collection — a gathering of artists, reflecting an array of musical influences that have migrated to the area: blues, gospel, classical, pop, and more. In the liner notes, Gwen Ansell (Director of the Institute for the Advancement of Journalism in South Africa) writes: “The persistent fractures in South African society were deliberately engineered by apartheid, results of an attempt to impose unitary, racially-constructed identities on all. All the tracks in this collection challenge that: they demonstrate the unifying power of collective hard music work.”

The whole collection is great, but “Umdali” is a stand-out for me, the song I keep clicking the back button on. In a press statement, the album’s co-creative director Siya Mthembu said of the track, “It comes back to the title of the album. [The song] is also about bringing a sense of indigenous knowledge to what we do and raising a salute to those who are the custodians of that knowledge.” — Janice Headley

KEXP's Digital Content team shares the music that's been in their personal rotation, both new and old.

KEXP's Digital Content team shares the music that's been in their personal rotation, both new and old.

KEXP's Digital Content team shares the music that's been in their personal rotation, both new and old.