With Rewind, KEXP digs out beloved albums, giving them another look on the anniversary of its release. In this installment, KEXP writer Dusty Henry delves into Nirvana’s final studio album In Utero for its 25th anniversary.

For the first time in my life, I find myself older than Kurt Cobain. I don’t try to consider that as any sort of landmark or some sought-after aspiration achieved. Mostly, it feels weird and wrong. After discovering the band – like many people – in my teens, Cobain felt like someone who’d lived a thousand lives in his 27 years. His music evoked pain and beauty, rawness and finesse, the perils of life and death. Maybe subconsciously I’d made it up that 27 years is all it took to understand these subtleties of the world around us. But here I am at 28 years old and still, as Cobain would say, bored and old.

No, I’m not old. Neither was Cobain when he sang that iconic line on “Serve The Servants,” the opening track to what would be Nirvana’s third and final album In Utero. His voice was always known for its creaks and breaks throughout his tenure in the spotlight, but there’s a different kind of apathy that I’ve always felt from Cobain’s voice when he sings those lines. He’s looking back at his teenage angst with a scoff, like someone who would roll his eyes at an embarrassing haircut from an old yearbook. His malaise for his past actions is sure to warrant a chuckle, considering that the chart-topping Nevermind with the undeniable angst anthem “Smells Like Teen Spirit” only came out two years before.

Those two years would’ve been the most tenuous of his life. He went from playing to empty rooms while supporting the band’s debut Bleach to becoming the face of an unprecedented cultural movement. MTV kept his videos in heavy rotation and his band would play a landmark gig at Reading Festival. He and his wife Courtney Love had a child, spurring a frenzy with the gossip rags hungry to exploit his and Love’s heroin addiction. I’m saying all of this like you don’t already know what I’m talking about. It’s hard not to know. That’s how ubiquitous the band still is. So if Cobain feels old and bored in 1993, it’s maybe warranted.

I couldn’t have really understood any of this when I first encountered Cobain’s music. My mother, bless her, didn’t hold me back from exploring Nirvana once I finally discovered it on my own. But she did openly worry that I not “worship false idols,” afraid that I might take to Cobain’s ethos too much. My grandfather was more blunt, openly calling Cobain a loser whenever it came up. All of this, of course, made it all the more appealing to me. Staring at the swirling circles of hell on the Bleach vinyl spinning on my thrift store turntable was only sort of metaphorical of the hypnotism the band would perform on me and had already performed on others. Nirvana tapped into an energy that was frightening, but relatable. A scared and angry part of our restless souls that we too often deny is there. And nowhere is that made more clear than on In Utero.

It’s hard to talk about In Utero 25 years after the fact, maybe even especially as someone who wasn’t cognizant enough to be aware of who Nirvana even was when the album came out. Nirvana has been repeatedly dissected, reexamined, and dissected perhaps more than any band of that era. There’s plenty to chew on with the enduring myth of Cobain, of how the band got the guy who wrote Songs About Fucking to produce their highly anticipated follow-up to Nevermind and trying to draw some lofty conclusions from a time in music when “alternative” became mainstream. At 28, I feel like I should have more answers and wisdom than Cobain did when he wrote the record. But I don’t. I wish I knew what it all meant. Or maybe it didn’t mean anything more than what people observed at the moment and what we all continue to observe in hindsight.

When I put the album on now, mostly I feel exhaustion. Not that I’m exhausted by the album, but that I can feel the weariness in Cobain’s voice and guitar. In Utero isn’t a document to look for “clues” about his impending suicide, which is a dangerous and harmful road for anyone to go down into. Stripped away from that context, In Utero does show us the portrait of a person who’s had too much and is unsure of what to do with it all. Again on “Serve The Servants,” he laments “there is nothing I could say that I haven’t thought before.” In this context, he’s referring to his strained relationship with his dad (he goes out of his way to prescribe him as a “dad” and not a “father”). The weight of his grief and anxiety relents to ambivalence. Even when his voice gravels and cracks, you still feel that exasperation creeping through in the slurs of his words. He’s at his most blase as he reflects on his parents’ “legendary divorce,” calling it “such a bore.”

“I swear to God, brother, it really isn’t as much as it seems,” Cobain told MTV in a 1994 interview discussing “Serve The Servants.” Aside from the opening lines referring to the zeitgeist of grunge, he assures the song isn’t about the media attention he and the band had been receiving (though he does consent that some stray lines will draw many people to make connections to his “past lives.” I assume he’s referring to the dad/father line). Specifically, he notes that he doesn’t want to come across as “whiny.” It speaks a lot to the climate of this era in Nirvana that he’d got out of his way to make these distinctions. Everything within Cobain’s orbit sparked controversy and over analysis. I mean, even his choice of wristwatch is still up for discussion. But in defense of the public, it’s hard to not want to make these connections to his personal life when it was so full on display in news racks across the country and blaring through radios and television sets.

In another world, that “I swear to God, brother” line would be canonized up there with his one-liners like “I’d rather be hated for who I am than loved for who I’m not.” It’s often glossed over just how funny he was on top of everything else. Even the way he deadpans the words “moderate rock” at the beginning of “Tourette’s” always gets a chuckle from me. He took his craft and art seriously but also had a sense of humor about it. Grunge was a punchline for him, despite continually being cited as a primary reason for its mainstream adoption. Releasing a noisy, no-way-this-could-be-a-single song like “Radio Friendly Unit Shifter” is a hilarious action when you’re the biggest band in the world dominating the FM waves.

Cobain’s humor almost makes more sense in 2018 than it did in 1993. Scroll through Twitter and you’ll find an onslaught of self-deprecating jokes about people’s own depression. @sosadtoday got a whole book deal out of being sad and impressively witty on the Internet. For a generation that grew up with Cobain’s lyrics already existing in the universe, I wonder if it may have had some effect on how we see the world. Fighting your inner demons doesn’t mean you lose some of these basic human tributes. It is, however, important to mention that this is still a cautionary tale. Sadness can be seductive and it can be consuming, and sometimes it’s hard to tell which is happening at any given time.

For as much as we can talk about Cobain’s trials, it’d be a mistake not to talk about this album on a purely musical. Because, my god, this album fucking rips. Nirvana’s trilogy of records is pretty unimpeachable, but In Utero finds in the band in their finest hour. Outside of bootlegged concerts, this would be the first time we really get to hear trio as “a band.” The record was recorded live in the studio with the coveted and cantankerous producer Steve Albini, utilizing minimal overdubs. In Utero feels like the version of Nirvana they’d always hinted out. Nevermind and Bleach are astounding works in their own right – the former a masterclass in translating punk fury into pristine studio recordings and the latter a wonderfully unruly and noisy take on pop dynamics. In Utero sits somewhere between those two realities of Nirvana.

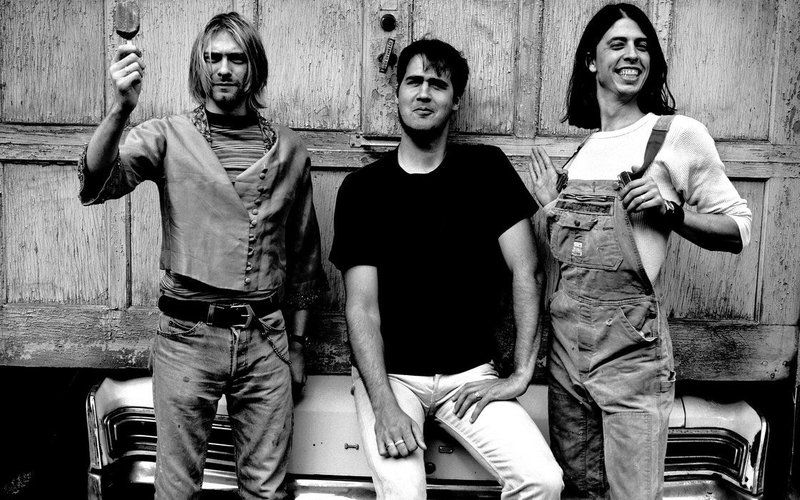

A discussion around Nirvana is almost always going to come back to Cobain (you may have noticed in the last like 1,000 words in this article), but drummer Dave Grohl and bassist Krist Novoselic do much more than playing a supporting role on In Utero. With the second track, “Scentless Apprentice,” we get the first and only instance of a songwriting credit for all three members. In another interview with MTV, Cobain credits Grohl with writing the drum pattern and guitar riff (though he also slips in that he initially thought the riff was “boneheaded”). The band sounds energized in a way they never have prior on record. You can almost feel the room shaking when Grohl pounds his snares and kick drum. If you’re ever looking for evidence as to why Grohl is so often mentioned as an all-time great drummer, throw on In Utero.

It’s not just how hard Grohl hits or the technique on display, but the intention he’s channeling through his sticks that stands out most. For all of his strengths during his tenure in Nirvana, it’s the way that he connected with Cobain’s songs that feels most notable. Plenty of drummers have power, but it takes a special type of musician to play with empathy toward the music. It’s one of the many facets (the rest I’ll get to in a second) that makes “All Apologies” so astonishing. In the band’s MTV Unplugged performance, much fuss is rightfully made about Grohl’s tasteful playing – but the album version of the song is just as wondrous to me. In what’s more or less a ballad, Grohl doesn’t sacrifice his trademark brute force but neither does he overpower the tenderness of the music. It’s a fine line to skirt, to be a behemoth and to be attuned to the room. His cymbals rattle and echo while he smashes into thunderous drum fills, leaving space for Cobain’s cries of “married/buried” somewhere amongst the clatter.

For his part, I’ve always seen Novoselic as the glue of Nirvana. Anecdotally, I hardly ever hear his name brought up in conversations talking about the “greatest bass players of all time.” It makes sense in a way, his style was never flashy enough to warrant that type of conversation. I’d argue that his watery, drowned out tone carries more influence than might be realized. Most of all though, Novoselic’s playing was always there to facilitate the music. He hardly ever gets moments to bask in the glory of the spotlight, aside from maybe his riffs on older cuts like “Love Buzz” and “Lounge Act.” Nor did he ever really seem like he sought out anything like that. Novoselic’s friendship with Cobain is long documented, dating back to their halcyon days in Aberdeen, Wash. Truly it seems like no one understood Cobain quite like Novoselic. I once heard him mention that to this day he still looks in pawn shop windows for left-handed guitars, a habit he built seeking out instruments for the Nirvana frontman to destroy on stage with minimal consequence. I get the same feeling when I think about that quote as I do when I pay close attention to his playing on In Utero. Between the pillars and legacies of Cobain and Grohl, Novoselic was a spiritual center of the band that wanted to support his friends and the music. (Also, how else were they going to get that insidious vibe of “Milk It” without him droning so heavily in those breakdowns? Underrated.)

For as much as I’ve listened to In Utero, for all the tumultuous energy exuded in the band’s performance, and for all the years we’ve collectively had to understand this record; we’ll never know what Cobain was feeling during this time of his life. No mysteries will be unlocked from another listen to “Heart Shaped Box” or deluxe packaging with demos and alternate takes. Admittedly, there’s an allure to Cobain’s ghost. It captured me when I first really learned of his music, years after his death. He left us with a short, but an undeniably fascinating body of work and a tragic death that still feels like too much to really process.

Cobain’s story is prime for projection; a scapegoat for our worst and most intimate feelings. So instead of looking at In Utero as a document of a time in Cobain’s life, maybe we should listen for ourselves in the music. The way he draws out the chorus in “Frances Farmer Will Have Her Revenge on Seattle,” a pained howl of “I miss the comfort in being sad,” how does that resonate with you? Surely Cobain’s not the only one of us who’s fetishized their own sadness. I know I have. But why do we do it? And why aren’t we honest with it? Searching in ourselves reveals part of what makes In Utero remarkable and maybe a little bit about Cobain in the process. The boldness to not just speak but actually scream your anxieties, knowing full well you have the world as your captive audience.

More than any song in Nirvana’s catalog, I come back to “All Apologies” the most. Knowing the history of the band, knowing Cobain’s suicide, and knowing that it’s the final track on the final album, it carries more weight than any Nirvana song as well. It’s a song that Cobain would refer to as being for his wife and his daughter, acknowledging that while the lyrics didn’t reflect that, the feeling did.

“What else should I be? All apologies,” he sings. Cellos rumble restlessly underneath his voice while he himself plays a spiraling riff, not unlike a music box or a lullaby. Again, we get some of Cobain’s humor as he scoffs at everyone else’s happiness – “What else could I say? Everyone is gay.” He wishes he could be like them, to be easily amused, but instead holds his pain even closer. The song erupts and dissipates again and again in typical Nirvana fashion. His voice sounds naked and vulnerable against the voluminous instrumentation. There’s that indefinable feeling in there that Cobain alludes to that feels like love. That he can’t solve his problems or anyone else’s, that maybe we should resign to the fact that “all in all is all we are.”

On the album’s 20th anniversary, I put on “All Apologies” on a walk home from work. The sky was dull grey while I walked underneath the Ballard bridge. I got a twisted feeling in my stomach. A realization that one day I would die, that it could happen today by a car swooping by or 80 years from now in a hospital bed. The only thing I could think to do at that moment was to take out my phone and text a couple of the people I care about most and tell them that I loved them. I didn’t feel sad and I didn’t long for death. But the melody of the song and the crescendos of the cellos stirred something in me – that I didn’t have to know what’s next or what anything means. That sometimes you can just feel something you don’t understand and that all that’s really important is to love.

In Utero is overwhelming. Even with the climactic and gorgeous ending of “All Apologies,” the album still doesn’t feel like a final statement. In an alternate universe, it’s a new starting point for the band. Just listen to an unearthed recording like “You Know You’re Right” and it only reopens the wound of what could’ve been. Yet it stands as the last completed studio recording from this band that only feels bigger the further away we get from their heyday. Aging doesn’t necessarily give clarity, just more questions. I feel that in In Utero now more than I did before.

On what would have been Kurt Cobain's 51st birthday, Martin Douglas reflects on a pivotal moment in his tumultuous young life, watching Nirvana's MTV Unplugged performance re-aired shortly after Cobain's suicide.

Back in 2008, our intrepid Review Revue Reviewer, Levi Fuller, took an in-depth look at the old KCMU vinyl for Nirvana's Nevermind. In celebration of the album's 25th anniversary, we revisit that blog post below.

As KEXP celebrates the 25th anniversary of Nirvana’s Nevermind, we asked our listeners to share their memories of this iconic release.You can still call us at 4124-GRUNGE (412-447-8643) and leave your story, too.